Story Telling and Threes

A Study of Repeating 3s

Story Tellers as of Aug. 26th, 2025

This page is intended as a consolidation of information generated by the Internet on this posted date. I recreated the images (sometimes adding color) and inserted some comments which I think are relevant. Whereas anyone might do the same, most people may not want to take the time. Sometimes I collated the initial AI response with the "dive deeper" selective option if there was enough of a difference to warrant inclusion but trying to prevent a wholesale redundancy. Let me again emphasize as I have stated multiple times elsewhere, I have no interest in plagiarizing anyone's work. Please give credit to the respective authors. While I sometimes get too busy with my handling of multiple sources of information and my fail to record this or that link or named author, it is regrettable and I apologize for any exclusion. I don't want to be caught using someone else's ideas or images and later be looked upon as a fool for trying to claim them as my own. Everyone deserves credit for their efforts.

Very often I come across different authors speaking to the ideas of origination and ancient usage of the "threes" repetition in different contexts, most of which are oriented towards an explanation of the "threes" occurrence in literature-related themes, to include movies, theater and typically art work in terms of paintings, but other are forms could be included as well as crafts and choreography, since we are dealing with a cognitive-generated influence that is not limited to limited to literature, art, or music. Indeed, it is of need to name a subject and identify the "how many, what kind(s), when, where, how often, etc..." three-patterned representations take place, as well as intermittancy, and the lack of a presence... and what instead is being used.

Establishing a field of research called Trichotomization to be academically, culturally, and colloquially recognized is helped by the fact that it already exists informally, by those who themselves have made note of the "threes" recurrence with or without the creation of a list of examples, because they rely heavily on a personal system of hyper-memory. While many people engage in such an activity, it is not typically directed towards an interest in "threes" or any number, and may prefer to have an undisclosed working memory needed for a workplace, creative thinking, or some communicative skill whether it is verbally executed or not.

Anyway, here's a small collection of threes-focused ideas concerning origination and uses. I took a moment this morning before starting on the recreation of multiple older webpages needing an update:

Internet query: "How old is the Rule of Three is an ancient principle of storytelling?"

AI response (using Opera browser): The storytelling "Rule of Three" is an ancient principle, with its roots tracing back to classical antiquity in both rhetoric and folklore. It is not a recent innovation, but a device that has been used for centuries across different cultures and communication mediums.

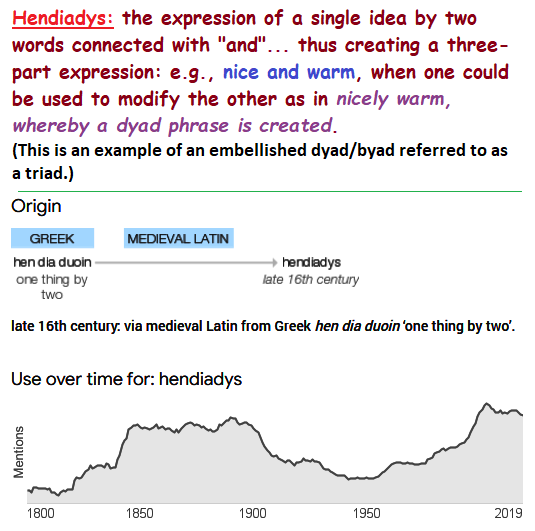

- The Rule of Three as a principle of communication is ancient, with roots in Ancient Rome and ancient Greece as early as the first millennium BCE, as indicated by the Latin phrase omne trium perfectum meaning "everything that comes in threes is perfect" and the Greek concept of hendiadys. The principle's use is also found in ancient texts, including religious and philosophical works.

- Religious and Cultural Texts: The number three holds a deep mystique and has been used for thousands of years to imbue a sense of power and completion in all aspects of culture, including religion and rhetoric.

- Origins in ancient rhetoric and philosophy:

- Rhetoric: It was widely used in Latin rhetoric to structure speeches and writings for maximum impact.

- Storytelling: The concept has been found in various cultures and many ancient stories.

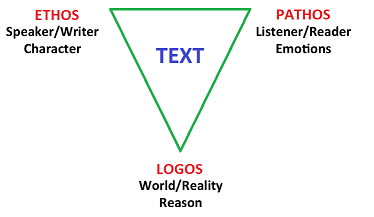

- Aristotle: The principle's earliest documented use comes from Ancient Greece. In his 4th-century BCE treatise Rhetoric, the

philosopher Aristotle discussed the three elements of persuasive rhetoric: ethos (credibility), pathos (emotion), and logos (logic). He

also identified three genres of public speech, recognizing that structuring arguments in threes was more effective.

- In his work Art of Rhetoric, referred to the use of "three types of speeches" and "three forms of proof".

- Ancient Rome: One of the most famous examples from this period is Julius Caesar's legendary quote, "Veni, vidi, vici" ("I came, I saw, I conquered").

- Ancient Greece: The Greeks also employed a similar concept called hendiadys, which uses three words to express a single idea, by using the word "and" as a conjunction between two words. (Single idea + Two words conjunctioned = Triadic expression)

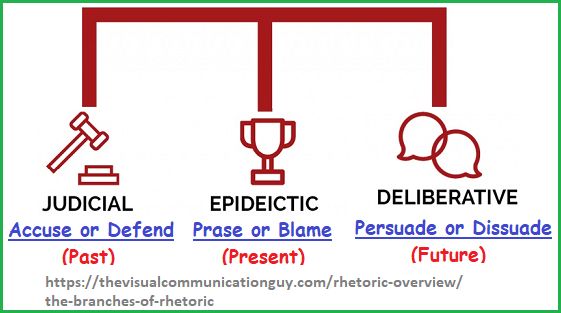

Aristotle's 3 types of Rhetoric, (AI generated information):

Aristotle identified three types of speeches, also called genres of rhetoric: deliberative, which persuades about future actions; forensic, which argues about past actions in a legal context; and epideictic, which aims to praise or blame in a present-day, ceremonial setting.

- Deliberative (Political) Rhetoric

- Purpose: To exhort or dissuade about actions that will happen in the future.

- Goal: To argue what is advantageous or harmful.

- Context: Political, legislative, and debates about future policies and actions.

- Forensic (Judicial) Rhetoric

- Purpose: To argue about past events.

- Goal: To establish the justice or injustice of actions that have already occurred.

- Context: Legal and court settings, involving accusations and defenses.

- Epideictic Rhetoric

- Purpose: To praise or blame.

- Goal: To highlight what is honorable or shameful.

- Context: Ceremonial occasions, such as a eulogy, an award speech, or a commendation, focusing on the present.

Internet query: "Aristotle's 3 Forms of Proof", (AI generated information):

Aristotle's three forms of rhetorical proof, or appeals, are logos (appeal to logic), pathos (appeal to emotion), and ethos (appeal to the speaker's credibility). Logos uses facts, statistics, and logical arguments to persuade; pathos aims to evoke an emotional response in the audience; and ethos builds trust by demonstrating the speaker's character, virtue, and goodwill. Together, these three appeals form the basis of persuasion and are still highly relevant in public speaking, writing, and even modern advertising and digital communication.

Teaching Text Rhetorically

- Logos (Logical Appeal)

- Logos is the use of facts, evidence, and logical reasoning to persuade an audience. It focuses on the message itself, making it clear, consistent, and well-supported by evidence.

- Strategies for using logos:

- Citing facts, data, and statistics.

- Providing a well-reasoned argument with a clear, specific thesis.

- Using logical connections, such as deductive and inductive reasoning.

- Pathos (Emotional Appeal)

- Pathos is the use of emotion to appeal to an audience's values, beliefs, and imagination. By evoking feelings like sympathy, anger, or excitement, a speaker can put the audience in a certain frame of mind that makes them more receptive to the argument.

- Strategies for using pathos:

- Telling powerful stories or anecdotes.

- Using vivid, emotionally charged language.

- Including images or visuals that evoke strong feelings.

- Ethos (Credibility Appeal)

- Ethos is the appeal to the speaker's character or credibility to build trust with the audience. Persuasion is more likely if

the audience believes the speaker is knowledgeable, trustworthy, and of good moral character.

- Strategies for establishing ethos:

- Highlighting relevant professional or academic qualifications.

- Demonstrating goodwill toward the audience and considering different viewpoints.

- Using appropriate, respectful language and maintaining a polished presentation.

- Ethos is the appeal to the speaker's character or credibility to build trust with the audience. Persuasion is more likely if

the audience believes the speaker is knowledgeable, trustworthy, and of good moral character.

Internet query: "How old is the Rule of Three is an ancient principle of storytelling?": (AI generated response)

- Roots in oral storytelling

- Fables and Folktales: The Rule of Three can be seen in classic fables, such as "The Three Little Pigs" and "Goldilocks and the Three Bears".

- Modern Communication: The principle remains popular today, used in advertising, writing, and public speaking to create more memorable and persuasive communication.

- Before written language was widespread, stories were passed down orally. Repetition was a crucial memory aid, and three was the minimum

number of elements needed to create a memorable pattern. This is why the rule is so prevalent in traditional folklore and fairy tales from

around the world:

- The Three Little Pigs

- Goldilocks and the Three Bears

- Three Billy Goats Gruff

- Three wishes granted by a magical entity

- In these stories, (just as in numerous jokes) the first two events often serve as a setup or build-up of tension, while the third provides the resolution, adds a twist, or delivers the punchline. [This is why some have emphacized the position that humans occupy the 3rd planet "as a punchline".]

- Vladimir Propp's "trebling" (Trebling or Tripling?["They

mean exactly the same thing, and both words started as "triplus" in Latin. "Treble" is more commonly used in British

English. In American English the word is used only in musical contexts..."])

- Russian folklorist Vladimir Propp, carried out a formal examination of this ancient structure in his 1928 book Morphology of the Folktale. He studied thousands of Russian folk-tales and identified a core structural element he called "trebling," or the repetition of a narrative element three times. This gave a modern name to the ancient tradition.

Internet Query: "How old is the ancient principle of storytelling?" (AI generated responses):

The ancient principle of storytelling is at least 50,000 years old and may be as old as language itself. The earliest stories were passed down orally and later through visual art, before the invention of writing.

- The oldest evidence of storytelling:

- Visual art... (~50,000+ years ago): The earliest physical evidence of stories being told comes from cave paintings that visually depict narratives. The oldest known example, discovered in an Indonesian cave, dates back over 50,000 years and shows three human-like figures hunting a wild pig. Other ancient visual stories have been found in the Chauvet and Lascaux caves in France, dating to about 30,000 to 36,000 years ago.

- Oral tradition... (~50,000+ years ago): Before writing, stories were communicated orally, using voice, gestures, and other performance elements to entertain and educate. Some of the world's oldest stories still exist today through oral traditions. For example, some Aboriginal Australian stories are believed to record events that occurred over 7,000 years ago.

- Written language... (~5,000+ years ago): The development of writing systems like Sumerian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphics allowed stories to be documented on portable media like clay and papyrus. The Epic of Gilgamesh, dating to around 2100 BCE, is one of the earliest surviving works of literature.

- The purpose of ancient stories:

- From the beginning, storytelling served as a fundamental tool for human connection and survival, not just entertainment. Ancient stories were created to:

- Explain the world: Myths and legends were used to explain how the world came to be, such as the Aboriginal Dreamtime stories.

- Impart wisdom: Tales like Aesop's Fables used animals to teach timeless moral lessons about human behavior.

- Establish social norms: In hunter-gatherer societies, stories were used to convey social etiquette and cultural values.

- Record history: Stories recorded monumental events, victories, and the deeds of kings and gods.

- Communicate across generations: For civilizations without writing, oral stories were a vital method for passing down history, traditions, and lessons to the next generation.

Internet query: "How old is the ancient principle of storytelling?" (AI generated response):

The ancient principle of storytelling is as old as human language and culture, with the earliest evidence dating back over 40,000 years. While a specific origin is impossible to pinpoint, its development is traced through the evolution of human communication.

- Timeline of ancient storytelling:

- 44,000 years ago: The start of visual storytellingThe earliest recorded story is a 43,900-year-old rock-art panel found in a cave on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. The painting depicts a hunting scene where human-like figures hunt pigs and dwarf buffalo.

- 50,000+ years ago: The age of oral traditionOral storytelling is thought to have existed for over 50,000 years, predating written language. Because stories were memorized and passed down, they were never fixed to a single version and adapted with each telling. Examples include:

- The Klamath people in Oregon orally passed down the story of the formation of Crater Lake for at least 7,600 years.

- Indigenous Australian oral narratives contain stories that accurately describe sea-level rises over 7,000 years ago.

- 3,400 to 5,400 years ago: The invention of writingWith the invention of writing by the Sumerians and Egyptians around 3,400 years

ago, storytelling could be recorded for the first time. This led to the creation of written epics, including some that originated as

oral traditions:

- The Epic of Gilgamesh was written around 2700 BCE, telling the story of an ancient Mesopotamian king.

- Homer's works, like the Iliad and the Odyssey, began as oral traditions recited by bards as early as the 12th century BCE before being preserved in writing centuries later.

- 2,500 years ago: The introduction of dramatic theoryAround 2,500 years ago, Greek philosophers like Aristotle formalized the principles of dramatic structure in works such as Poetics. He established foundational story components, including plot, character, and thought, that are still studied today.

- The enduring purpose of storytelling:

- For tens of thousands of years, storytelling has remained a constant pillar of human culture, regardless of the medium. It has

always served fundamental human needs:

- Transmitting knowledge and history: Stories teach people how to navigate the world, preserve cultural heritage, and transmit critical information to future generations.

- Shaping cultural identity: Storytelling has been used to explore the human experience and help people make sense of the world and their place within it.

- Connecting with others: Stories serve as a form of social connection, allowing humans to better understand one another. Oral traditions, passed down around a fire, fostered a sense of community.

- For tens of thousands of years, storytelling has remained a constant pillar of human culture, regardless of the medium. It has

always served fundamental human needs:

Origination: Tuesday, Aug. 26th, 2:00 AM

Date of initial posting: Tuesday, Aug. 26th, 6:12 AM