page 25

Progressive Thinkers as of 12/1/2022

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Why should there be a discipline such as epistemology (study of knowledge)? Aristotle (384–322 BC) provided the answer when he said that philosophy begins in a kind of wonder or puzzlement. Nearly all human beings wish to comprehend the world they live in, and many of them construct theories of various kinds to help them make sense of it. Because many aspects of the world defy easy explanation, however, most people are likely to cease their efforts at some point and to content themselves with whatever degree of understanding they have managed to achieve.

Unlike most people, philosophers are captivated—some would say obsessed—by the idea of understanding the world in the most general terms possible. Accordingly, they attempt to construct theories that are synoptic, descriptively accurate, explanatorily powerful, and in all other respects rationally defensible. In doing so, they carry the process of inquiry further than other people tend to do, and this is what is meant by saying that they develop a philosophy about these matters.

The origins of knowledge

Philosophers wish to know not only what knowledge is but also how it arises. This desire is motivated in part by the assumption that an investigation into the origins of knowledge can shed light on its nature. Accordingly, such investigations have been one of the major themes of epistemology from the time of the ancient Greeks to the present. Plato's Republic contains one of the earliest systematic arguments to show that sense experience cannot be a source of knowledge. The argument begins with the assertion that ordinary persons have a clear grasp of certain concepts—e.g., the concept of equality. In other words, people know what it means to say that a and b are equal, no matter what a and b are. But where does such knowledge come from? Consider the claim that two pieces of wood are of equal length. A close visual inspection would show them to differ slightly, and the more detailed the inspection, the more disparity one would notice. It follows that visual experience cannot be the source of the concept of equality. Plato applies this line of reasoning to all five senses and concludes that such knowledge cannot originate in sense experience. As in the Meno, discussed above, Plato concludes that such knowledge is "recollected" by the soul from an earlier existence.

It is highly significant that Plato should use mathematical (specifically, geometrical) examples to show that knowledge does not originate in sense experience; indeed, it is a sign of his perspicacity. As the subsequent history of philosophy reveals, mathematics provides the strongest case for Plato's view. Mathematical entities—e.g., perfect triangles, disembodied surfaces and edges, lines without thickness, and extensionless points—are abstractions, none of which exists in the physical world apprehended by the senses. Our knowledge of such entities, it is argued, must therefore come from some other source.

Innate and acquired knowledge

The problem of the origins of knowledge has engendered two historically important kinds of debate. One of them concerns the question of whether knowledge is innate—i.e., present in the mind, in some sense, from birth—or acquired through experience. This matter has been important not only in philosophy but also, since the mid-20th century, in linguistics and psychology. The American linguist Noam Chomsky, for example, has argued that the ability of young (developmentally normal) children to acquire any human language on the basis of invariably incomplete and even incorrect data is proof of the existence of innate linguistic structures. In contrast, the experimental psychologist B.F. Skinner (1904–90), a leading figure in the movement known as behaviourism, tried to show that all knowledge, including linguistic knowledge, is the product of learning through environmental conditioning by means of processes of reinforcement and reward. There also have been a range of "compromise" theories, which claim that humans have both innate and acquired knowledge.

Rationalism and empiricism

The second debate related to the problem of the origins of knowledge is that between rationalism and empiricism. According to rationalists, the ultimate source of human knowledge is the faculty of reason; according to empiricists, it is experience. The nature of reason is a difficult problem, but it is generally assumed to be a unique feature or faculty of the mind through which truths about reality may be grasped. Such a thesis is double-sided: it holds, on the one hand, that reality is in principle knowable and, on the other hand, that there is a human faculty (or set of faculties) capable of knowing it. One thus might define rationalism as the theory that there is an isomorphism (a mirroring relationship) between reason and reality that makes it possible for the former to apprehend the latter just as it is. Rationalists contend that, if such a correspondence were lacking, it would be impossible for human beings to understand the world.

Almost no philosopher has been a strict, thoroughgoing empiricist—i.e., one who holds that literally all knowledge comes from experience. Even John Locke (1632–1704), considered the father of modern empiricism, thought that there is some knowledge that does not derive from experience, though he held that it was "trifling" and empty of content. Hume held similar views.

Empiricism thus generally acknowledges the existence of a priori knowledge but denies its significance. Accordingly, it is more accurately defined as the theory that all significant or factual propositions are known through experience. Even defined in this way, however, it continues to contrast significantly with rationalism. Rationalists hold that human beings have knowledge that is prior to experience and yet significant. Empiricists deny that this is possible.

The term experience is usually understood to refer to ordinary physical sensations—or in Hume's parlance, "impressions." For strict empiricists this definition has the implication that the human mind is passive—a "tabula rasa" that receives impressions and more or less records them as they are.

The conception of the mind as a tabula rasa posed serious challenges for empiricists. It raised the question, for example, of how one can have knowledge of entities, such as dragons, that cannot be found in experience. The response of classical empiricists such as Locke and Hume was to show that the complex concept of a dragon can be reduced to simple concepts (such as wings, the body of a snake, the head of a horse), all of which derive from impressions. On such a view the mind is still considered primarily passive, but it is conceded that it has the power to combine simple ideas into complex ones.

But there are further difficulties. The empiricist must explain how abstract ideas, such as the concept of a perfect triangle, can be reduced to elements apprehended by the senses when no perfect triangles are found in nature. He must also give an account of how general concepts are possible. It is obvious that one does not experience "mankind" through the senses; yet such concepts are meaningful, and propositions containing them are known to be true. The same difficulty applies to colour concepts. Some empiricists have argued that one arrives at the concept of red, for example, by mentally abstracting from one's experience of individual red items. The difficulty with this suggestion is that one cannot know what to count as an experience of red unless one already has a concept of red in mind. If it is replied that the concept of red and others like it are acquired when we are taught the word red in childhood, a similar difficulty arises. The teaching process, according to the empiricist, consists of pointing to a red object and telling the child "This is red." This process is repeated a number of times until the child forms the concept of red by abstracting from the series of examples he is shown. But these examples are necessarily very limited: they do not include even a fraction of the shades of red the child might ever see. Consequently, it is possible for the child to abstract or generalize from them in a variety of different ways, only some of which would correspond to the way the community of adult language users happens to apply the term red. How then does the child know which abstraction is the "right" one to draw from the examples? According to the rationalist, the only way to account for the child's selection of the correct concept is to suppose that at least part of it is innate.

"epistemology." Encyclopædia Britannica, 2013.

I have a bit of a problem with the foregoing comment about there not being examples of a "perfect" triangle in Nature. It all depends on how strict the term "perfect" it to be interpreted. Since we have triangular mountain peaks, the Triangle of a nose, the triangle of pine trees, the triangular path of the Sun over the course of day, triangular spider web spaces, triangular finger spaces, V-shaped flight formations of migrating birds, etc., we can not say that no model of a triangle exists. To say "perfect" is on the order of saying words such as "beautiful, smart, rich, healthy, etc..." It's rather a matter of opinion and not actually due to measuring something according to that which one is seeking but claims it doesn't exist except in the language of a person who is using it as an attempt to indicate they are thus exceptional as well... for bringing it to mind and verbalizing it as an argument which can not be toppled as if one is playing a child's game of "king of the hill".

Without a doubt, a study of Philosophical concepts is necessary when discussing language. Since language tends to involve multiple views for which there seems not to be any tangible confirmations of a given theory, we are left with ascertaining the closest truth about language as an approximation... until such time as there are views which enable them to be empirically tested in both a laboratory and real world setting (in as much as humanity defines such settings). It is an approximation which must contend with the views consistently placed under the dichotomous rubric of Nature/Nurture, though various labels are employed for one or another context. There is yet no application of a Trichotomous rubric because the mind of humans have not recognized a 1-2-3... developmental sequence being used by human cognitive activity which incessantly appears to be stuck, spinning its wheels, in the framework of a two-patterned orientation. It is like a person who finally manages to get out of quicksand, only to re-enter it because they either can't believe they managed to get out or want to convince themselves that it is possible to get out.

In short, the argument over language theories is whether or nor a capacity for language is innate... in other words, something all humans are born with, or is it due to one or more external factors which create a suitable and acceptable environment for channeling exhortations into a concentrated activity which we later call language. And if there were no external pressures or influence, one might argue, language would not exist... because the act of making a sound out of one's mouth is not necessarily to be described as a language... such as when one snores, coughs, sneezes or one uses the other end to expiate some rather sinful discursive which all people anywhere in the world are quite familiar with. Just because we call one end of the physical spectrum a mouth and the other an anus does not mean only the sounds emitted from the mouth are to be designated a language. Surely the quantity and quality of anal expulsions speaks volumes of information about a person... like what they ate, state of health, or whether they excuse themselves while in the presence of others who seek out a gas mask.

Understanding language in its multiple forms requires one to have lots of knowledge. They must often play the Devil's Advocate to their own ides because there may not be another conveniently nearby who as a similar level or type of knowledge with whom to discuss such ideas. But such a tactic can lead to rationalizations of support unless one is attuned to such a trap and arms themselves with an enlarged set of tools to be used to investigate, dissect and contemplate possible conclusions labeled as truth, that itself must be subjected to the same level of critiquing which includes an awareness of that debilitating character called second guessing. Such a fellow can sit on one's shoulders so heavily as to prevent a person from ever revealing what they have found to a given point in their studies. In such circumstances far too many otherwise quite excellent researchers find themselves crying Uncle! and give up. I have given up on several occasions, or at least effectively tricked that burdensome fellow who seeks to pin me to the mat, and come back with a new wrestling hold or even scare tactic, in name or garment of disguise. Three rounds in a three-rope ring or not, I am not down for the count. My tag-team trio of opponents called scurrilous self-doubt, contemporaneous corporeal cul de sacs and dastardly disingenuous distraction do not know the tricks I have learned to employ in countering their singular or collective moves which include cheating when the "referee" (consciousness) is otherwise engaged in day dreaming, wistful embarkations, and desultory escapades.

It is important for us to look at the study of knowledge and have at least some, even (know-it-all) puerile conception of what the word, as an idea, means so that at some future time we can exercise that bit of wisdom endowed by the aging process which permits... and even expects more lengthier moments of reflection and an aptitude for a level and type of humility designated as an honest assessment of our own ignorance. Since knowledge involves that thing which we think are describing as language and such an activity is assumed to provide us with some semblance of empowerment... whether justly deserved or not... let us take a short gander at the topic, just for the fun of walking along its cobblestone path (created by a need of having so many different types of footfalls... with or without footwear), if nothing else:

Like most people, epistemologists (those interested in the study of knowledge) often begin their speculations with the assumption that they have a great deal of knowledge. As they reflect upon what they presumably know, however, they discover that it is much less secure than they realized, and indeed they come to think that many of what had been their firmest beliefs are dubious or even false. Such doubts arise from certain anomalies in our experience of the world. Although several of these anomalies are discussed below in the section on the history of epistemology, two in particular will be described in detail here in order to illustrate how they call into question our common claims to knowledge about the world.

>There are two conventional long-standing problems concerning knowledge, but I shall add a third due to the present discussion on Language:

- Problem 1: Knowledge of the external world

- The problem consists of two issues: a) how one can know whether there is a reality that exists independently of sense experience, given that sense experience is ultimately the only evidence one has for the existence of anything, and b) how one can know what anything is really like, given that different kinds of sensory evidence often conflict with each other.

- Problem 2: The other-minds (the individual mind of others)

- Each human being is inevitably and even in principle prevented from having knowledge of the minds of other human beings. Despite the widely held conviction that in principle there is nothing in the world of fact that cannot be known through scientific investigation, the other-minds problem shows to the contrary that an entire domain of human experience is resistant to any sort of external inquiry. Thus, there can never be a science of the human mind.

- An example of this idea about having a different mind with respect to language or more exact... a vocal expression, is found in the comment that different people in the world are said to hear the bark of a dog in a different way, whereby they report a different kind of sound being made. (For instance, a dog's bark is heard as au au in Brazil, ham ham in Albania, and wang, wang in China. In addition, many onomatopoeic words are of recent origin, and not all are derived from natural sounds.) How are we to confirm or deny this, and more importantly, if this is true not only of sounds but other sensory data, are we in the midst of several different realities or dimensions of a single reality?

- Problem 3: A definition of Language

- Do the perceptions of all senses describe a type of language?

- Are all sounds to be described as a language?

- Are all languages a form of communication?

- Are all communications to be interpreted as messages?

- Are all messages in the form of a describable pattern?

- Is the absence of a pattern also a pattern or are we engaging in a stereotypical cognitive activity of dichotomization?

- Does nature engage in multiple forms of patterns, and these can be labeled a type of language?

- Do all patterns describe a type of communication, but not necessarily a communication intended for humans?

- Are the patterns discovered in use by Nature, primarily intended by and for Nature, but that humans have intercepted such communications and decided to interpret them in terms of a human-centered regard?

First two problems listed were culled from: "epistemology." Encyclopædia Britannica. The third one was created off the top of my head as I was compiling the first two.

While I have it in mind, since my mind was engaged in the contemplation of vowels and consonants as I lay in bed and I have traversed the path before, let me list the vowels and consonants as a simple beginning:

Vowels: A, E, I, O, U... and sometimes Y

Consonants: B, C, D, F, G, H, J, K, L, M, N, P, Q, R, S, T, V, W, X, Z

Now, let me sort them according to simple sound-alike dispositions called rhymes:

- A, J, K

- B, C, D, E, G, P, T, V, Z

- F

- H

- I, Y

- L

- M, N

- O

- Q, U

- R

- S

- W

- X

Let us now look at the first numbers of a counting sequence to note the absence of rhyme:

- One

- Two

- Three... This third item provides the same sound heard in the naming convention used by children where an "e" sound was previously referenced. Indeed, in English we also have "Mommy" (Motherly) and "Daddy" (Fatherly) as "e" sounds as well, with the sometimes used Mammy, grandmammy, grandpappy; and "auntie" but no "unclie" or sistery, brothery, cousinie. However, one might at sometime hear the words "Brotherly" and "Sisterly" in a religious context.) We might also encounter someone saying the word "wifey" (for a wife), but no similar "husbandy" for husband.

- Four

- Five

- Six

- Seven

- Eight

- Nine

- Ten

- Eleven

- Twelve,

- "7- teens" as rhymes: 13, 14, 15, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19

- Then we meet with an "e" sound with all numbers up to ninety-nine: twenty, thirty, forty, fifty, sixty. seventy, eighty, ninety.

If we resort to include the numerical designation of counting the first few numbers, we have the following where the first three counts do not rhyme but thereafter we encounter a repetition, which provides us with a 3 -to- 1 ration situation:

- 1st

- 2nd

- 3rd

- 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th...etc.

At this juncture, let me reference a commonality of naming encountered in childhood, though this may well differ for languages other than English because of naming conventions. What I want to point out that in my experiences while in the U.S., is that very often we find children being named in such a way as to produce the dominant sound category, and that this rhymes with the number "three", and not third, thrice, triple, triune, triad... though some names may offer some approximation to such sounds such as "Brad" and "triad", though the name "bradly" might be encountered in some cases.

For example, let us take a list of common 1st or given names I have come across in English usage, where boys names are more applicable than some girls names to be rendered with the "e" sound, though nicknames (or a person's middle or last name) might be employed in order that someone be provided with an "e" sound:

- Andy, but not Alice

- Betty, but not Bo

- Charlie, but not Carol

- Debbie, but not Darryl

- Eddy, but not Eva (though "Evie" might be used)

- Frankie (for girl or boy), but not Fabian

- Gary, but not Gertrude

- Hillary, but not Hank

- Issac-i-al (or Ignac-i-o), but not Iris

- Jackie, but not Jack

- Kily (Kylee), but not Karen

- Larry, but not Lisa

- Mary, but not Marvin

- Newbie, but not nerd (however, there is "nerdy")

- Oakley (Oakleigh), but not Oswald

- Pete-y, but not Pandora

- Queenie, but not Quinton

- Ricky, but not Rachel

- Sandy, but not Simon

- Terry, but not Terrance

- (h)Ughie ("h" in hugh is silent, emphacising the "U" and "e"), but not Ursalla

- Vicky, but not Victor

- Wally, but not Wanda (unless "wandie" or wandy is used)

- le (X)i, or ale-X-i-a ("X" letter is emphasized along with "e" sound), but not Alex (for a boy) (I do know of someone named XYZick who preferred to use his middle name)

- "Y" very often used internally or at the end of a name and may be pronounced as the "e" sound (Not commonly associate with a first name)

- Zachary, Zoe/Zoey/Zoie, but typically found with a girl's name that may or may not express an "e" sound

Sources (other than from memory), and let me note that a lot of names do not exhibit an "e" ending sound, but may acquire one... and in addition, it must be wondered if there used to me more... or less... usage of names amiable to being transformed into an "e" sounding word, and why do children continue to do so?:

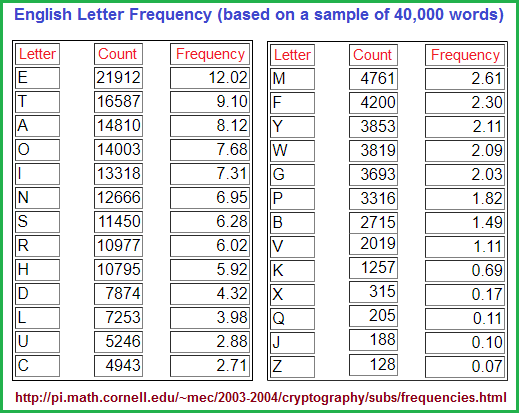

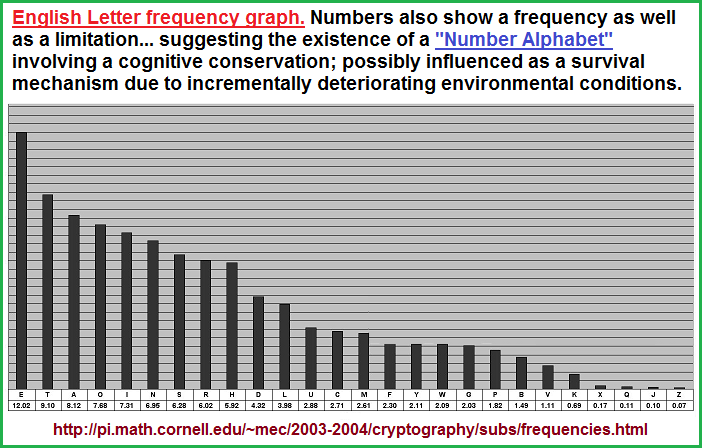

If we can claim that words can sometimes be used as expressions of number, whether we are aware of it or not, then the usage of an "e" sound may be reflective of its expression, at least in some English language uses. A review of letter frequencies needs to be included at this point, in order to establish the fact (for a given sampling), that the letter "e", which rhymes with "three" is the dominant repetition:

Date of (series) Origination: Saturday, 14th March 2020... 6:11 AM

Date of Initial Posting (this page): 9th January 2023... 12:08 AM AST (Arizona Standard Time); Marana, AZ.