Visitors as of Sept. 3rd, 2025

On this page in order of appearance:

- Tripartite Aspects of Parallel Universes: [1]

- Tripartite concepts of mind and brain: [2] (Abstract of work by Lazaros C. Triarhou, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki)

- The Brain Is Adaptive Not Triune: [3] (Abstract of work by Patrick R Steffen, Dawson Hedges, Rebekka Matheson)

- Tripartite Aspects of brain development from insects to humans: [4]

- Tripartite Aspects of brain neurons: [5]

- Tripartite Aspects of Jungian Archetypes: [6] (Jung was influenced by Freud's Tripartite ideas.)

- Tripartite Aspects of Jung's interpretation of the Trinity: [7]

- (The word "reinterpretation" was discarded by the AI.)

Carl Jung, like Georges Dumezil did not consider the "4" or "forth" in terms of a developmental cognitive profile (which I describe as a 3-to-1 ratio)... reflecting a potential developmental shift in consciousness with a maturity developmentally expressed in terms of a fusion, such as the symbolically expressed "3 persons in 1 god" idea in Christianity; which symbolically reflects the ongoing incremental "fusion" of the Sun's three phases/"moments" (dawn- noon- dusk) as the Earth's rotation slows and the Sun expands. Also notice how Jung's maturational development sequence of a 3-stage psychological process reflects the the 1-2-Many theme of humanity's early efforts at developing a counting system... as well as the symbolic structure of a basic family unit, where the female enters into the group with the term "animus."

[1] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects of Parallel Universes"

AI (overview) response: While no formal theory is called the "Tripartite Aspects of Parallel Universes," the phrase can be used to describe three of the most discussed and distinct types of multiverses proposed by physicists, such as cosmologist Max Tegmark. These are extensions of our observable universe, alternate bubble universes, and the "many-worlds" of quantum mechanics.

Level I: Extended infinite spaceThis is the most straightforward and least controversial type of parallel universe, based on the assumption that space is infinite or near-infinite.

- How it works: If the universe stretches on infinitely, then every possible arrangement of matter within a region the size of our observable universe must repeat an infinite number of times.

- What it implies: In this scenario, there are identical "you"s living on identical Earths with identical solar systems, though they are an unimaginably vast distance away from us. We cannot observe them because they exist beyond our cosmic horizon, the limit of how far light has had time to travel to us since the Big Bang.

- Key distinction: These parallel universes have the same physical laws and constants as our own. They differ only in their initial conditions—the specific arrangement of matter and energy.

Level II: Different physical laws and constants

This type of multiverse comes from the theory of "eternal inflation." This theory suggests that the chaotic expansion of space after the Big Bang created many bubble universes.

- How it works: According to eternal inflation, space keeps expanding, but some areas stop stretching and form distinct bubbles, each with its own Big Bang. These bubbles may have different physical laws, numbers of dimensions, and constants due to spontaneous symmetry breaking.

- What it implies: The universe is one of these bubbles, and others exist with different properties. In some, the speed of light or the strength of gravity could be completely different.

- Key distinction: Unlike Level I universes, the difference is not just in the arrangement of matter but also in the fundamental rules that govern physics itself.

Level III: The many-worlds of quantum mechanics

This concept is a direct result of the many-worlds interpretation (MWI) of quantum mechanics. It suggests that when a quantum event has multiple possible outcomes, all of them occur, each in a separate, newly created universe.

- How it works: The universe's quantum state is a wave function that continually branches, with each branch representing a different outcome. When someone observes a quantum event, they only experience one of these branches. The others continue to exist as parallel realities.

- What it implies: There are parallel versions of someone for every quantum decision or event that has ever occurred. If someone flipped a coin, one version of that person saw it land on heads, while another version in a parallel universe saw it land on tails.

- Key distinction: These universes are not spatially distant from us like Levels I and II. They occupy the "same space and time" but exist in different, non-interacting quantum branches. While this may sound like the most extreme form of a multiverse, Tegmark argues that it adds no fundamentally new types of universes beyond those in Level I, since any quantum possibility that exists in a Level III universe would also be realized in one of the infinite Level I universes

H.O.B. note: In other words, Tegmark's idea is just another variation of the 3-in-1 cognitive theme.

[2] Internet query: "Tripartite concepts of mind and brain"

Abstract: The 'triune brain', conceived by Paul D. MacLean (1913-2007) in the late 1960s, has witnessed more attention and controversy than any other evolutionary model of brain and behavior in modern neuroscience. Decades earlier, in his book Elements of Neurobiology published in 1923 in La Plata, Argentina, neurobiologist Christfried (Christofredo) Jakob (1866-1956) had formulated a 'tripsychic' brain system, based on his deep understanding of biological and neural phylogeny. In a historical context, 1923 was also the year of publication of Sigmund Freud's The Ego and the Id, whereby the founder of psychoanalysis solidified his Tripartite model of the mental apparatus. Tripartite systems of the human mind have been surmised since Plato and Aristotle; they continue to our era, an example being Robert J. Sternberg's triarchic theory of human intelligence. In view of the fact that both Jakob and MacLean invested a considerable part of their long and distinguished careers studying comparative, and particularly reptilian neurobiology, the present article revisits their neuroevolutionary models, underlining the convergence of their anatomical-functional propositions, in spite of a time distance of almost half a century.

Introduction: In the words of neurologist William E. DeMyer [1], "to understand the brain–thought–behavior triumvirate is the Holy Grail of neuroanatomy, as compelling to the researcher as a cyclonic vortex." Models to explain the mechanisms of operation of the human mental apparatus have been formulated since the era of classical Greece. The preponderance of such models appear to be 'Tripartite,’ without necessarily entailing that e.g. unipartite, bipartite or quintopartite models would be less meaningful.

[3] Internet query: "The Brain Is Adaptive Not Triune"

Abstract: Theory impacts how research is conducted. A popular theory used to conceptualize brain functioning is the triune brain theory. The triune brain theory is an evolutionary theory of brain development that emphasizes three key brain regions consisting of the brainstem, the limbic system, and the cortex that function relatively independently in coping with stress via fight or flight, emotion, and cognition, respectively. However, modern neuroscience research demonstrates that the triune brain theory does not accurately explain how the brain functions in everyday life or during the stress response. Specifically, emotion and cognition are interdependent and work together, the limbic system is not a purely emotional center nor are there purely emotional circuits in the brain, and the cortex is not a purely cognitive center nor are there purely cognitive circuits in the brain. We propose a new evolutionarily based model, the adaptive brain, that is founded on adaptive prediction resulting from interdependent brain networks using interoception and exteroception to balance current needs, and the interconnections among homeostasis, allostasis, emotion, cognition, and strong social bonds in accomplishing adaptive goals.

Introduction: From the perspective of the triune-brain theory, these three brain regions evolved separately and function somewhat independently: the basal ganglia and brain stem are involved in movement and basic life functions, the limbic system is involved in emotional responses that are seen more prominently in mammals as compared to reptiles, and the cortex is involved in cognition and executive functions and is most prominent in humans. In this perspective, evolutionary development begins with basic behavioral responses, then adds emotional responses that can alter these basic responses when threat or challenges arise, and then adds on cognition to alter emotional responses using reason, logic, and planning.

- There are several key problems, however, with the triune brain theory. First, the brain did not evolve in successive stages as MacLean hypothesized. The idea that vertebrate evolution has consisted of "newer brain structures being superimposed over and on top of 'older' brain structures, tracking development of complex cognition," is not evolutionarily justifiable. Basic neural regions are shared among all vertebrates. Where they differ is in proportion and extent. Just as an elephant's trunk is not a new structure superimposed over a snout but rather is an analogous structure differing in proportion (and consequently, in functional adaptation to the animal's needs), the human brain is not superimposed on a reptile brain but consists mostly of proportionally different analogous structures. Furthermore, the gradation of proportional shifts is not necessarily a linear progression from reptile to human.

- Second, brain structures do not function independently of one another. During emotional responses, there is activity in the amygdala and in the limbic system, but there is also activity in cortical areas and in the brainstem. Additionally, emotion and cognition are not independent events; rather, they are interrelated functions working in concert. For example, Bush et al. and Shackman et al. both note that emotional responses and cognitive responses in the cingulate cortex are interconnected and not separate as previously believed. Perhaps more importantly, the limbic system is not a purely emotional center in the brain. LeDoux notes that the hippocampus is considered part of the limbic system but that it is not considered an essentially emotional brain region; instead, it is a key area involved in memory, which is more closely associated with cognition. Because of these and similar problems, the term "limbic system" is no longer a commonly used term to describe how the brain functions.

- Limbic system" also loses its utility in a clinical setting; because affect is a culmination of a wide range of interrelated processes, including synthesis of internal and external stimuli, arousal, and memory, approach to disorders characterized by affect dysregulation is limited by the triune brain approach. And, finally, the brain does not act by simply responding to a stimulus. Instead, it predicts internal and external needs and adapts accordingly. Incoming stimuli interact with the current state in which the brain is.

- Third, current neuroscience research findings provide further evidence of the inaccuracy of triune brain theory and open new ways of understanding how the brain responds to stress and adapts to changing internal and external environments. Fear research provides an instructive specific example. There is no fear brain circuit that turns on during a fear response but otherwise lies dormant. Brain networks always have some level of activity that affects how they process incoming information. What changes is the relative activity of different brain networks, with networks being differentially activated based upon need. As these findings show, triune-brain theory does not match current research findings and using triune-brain theory as a general theoretical approach can lead to faulty hypothesis creation and poorly developed studies.

A more useful evolutionary theory of how the brain works needs to integrate accurate knowledge of brain structure and function. Adaptation, survival, and reproduction are at the heart of evolutionary theory, and interdependent brain networks have evolved to increase adaptation to be able to survive and reproduce. Further, emerging findings suggest that the brain uses interoceptive and exteroceptive information to predict future conditions and needs to enable optimal adaptation to continuously changing internal and external environments. Based on better understanding of how the brain works, we propose replacing "triune brain" with a term that better captures current understanding of brain function: the adaptive brain. In this conceptualization, the term adaptive brain emphasizes the interdependence and plasticity of brain regions and the brain's ability to predict and adapt to future needs and conditions. Instead of three relatively independent brain regions, or any number of independent brain regions, brain networks work together interdependently; instead of purely "emotional circuits" or "cognitive circuits," the brain uses interconnected networks to optimize maintenance of the body's internal state, emotion, and cognition to adapt to continuously changing needs. The brain's summated approach to these priorities regulates affect, and dysregulation of these interdependent circuits has important implications for psychopathology.

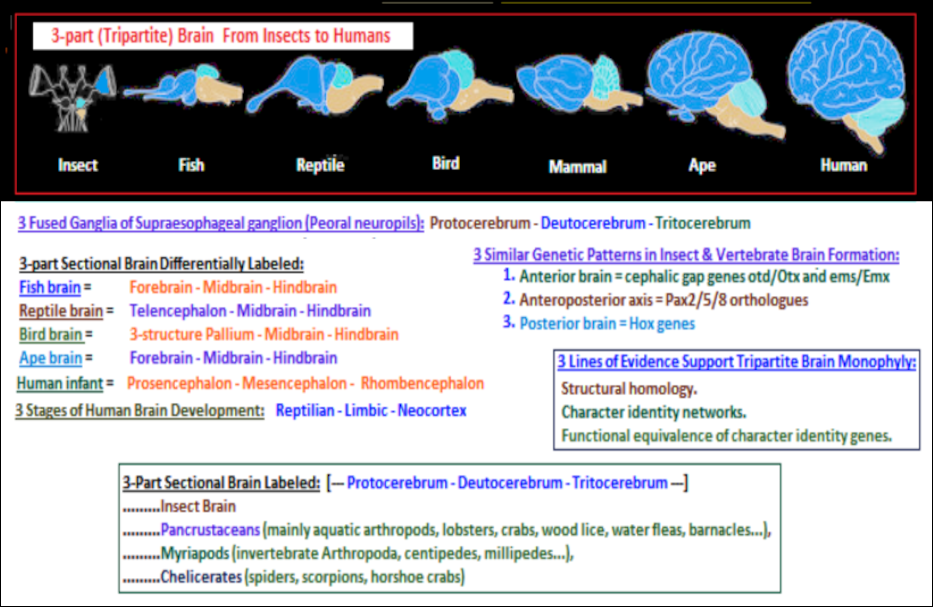

[4] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects of brain development from insects to humans"

AI (overview) response:

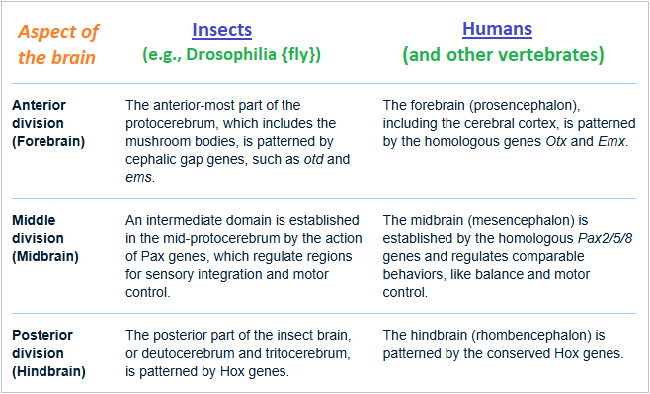

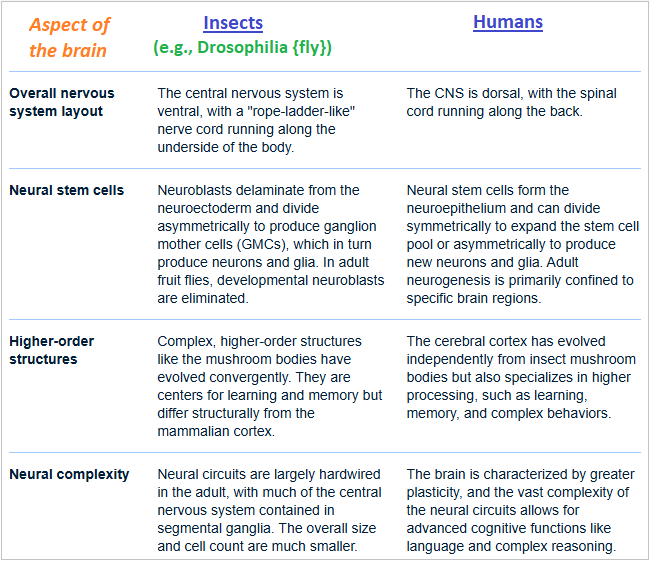

- To understand the Tripartite aspects of brain development from insects to humans, we must consider the deep evolutionary history of the nervous system. Though insect and human brains appear vastly different, research reveals striking similarities in the underlying genetic programs and developmental strategies that arose from a common bilaterian ancestor more than 600 million years ago.

- The term "Tripartite" refers to the three primary anterior-posterior (front-to-back) divisions of the brain that form early in embryonic development, regulated by a conserved genetic toolkit. While the gross structures of insect and human brains diverge significantly, these three basic divisions are patterned by homologous genes in both species, demonstrating a shared ancestry.

2. Conserved genetic mechanisms

The similarities in the early patterning of the insect and human brain demonstrate that the basic genetic machinery for building a complex central nervous system (CNS) evolved only once.

- Otx and Emx genes: These cephalic gap genes control the formation of the anterior brain. Cross-phylum experiments show that the otd and ems genes from insects can functionally replace their mammalian counterparts, Otx and Emx, in embryonic brain patterning.

- Hox genes: These homeobox genes define the anterior-posterior axis and determine the identity of the brain's posterior regions in both insects and vertebrates.

- Signaling pathways: Conserved pathways, such as Notch and Decapentaplegic/Bone morphogenetic protein (Dpp/Bmp), control the initial formation of the neuroectoderm and the specification of neural stem cells in both animal groups.

- Neurogenesis controls: While the adult brains look very different, the genes that control neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation, like Notch, are highly conserved.

3. Divergence in later development

While the fundamental, early-developmental toolkit is conserved, the overall architecture and developmental processes diverged significantly over millions of years, leading to specialized structures.

Here is the response I got the second time I entered the query making sure the input read "Tripartite Aspects of brain development from insects to humans" and not "Tripartite Aspects ofbrain development from insects to humans":

AI (overview) response: Brain development in both insects and humans follows a Tripartite blueprint, meaning the brain is organized into three principal, segmented parts that arise during embryonic development. Research has revealed that this fundamental plan is executed by a set of ancient, homologous genes, suggesting a common evolutionary origin in a shared ancestor over 500 million years ago. However, the physical structure, size, and complexity of the resulting brains have diverged dramatically.

Shared Tripartite developmental blueprintDespite their vast differences, the underlying developmental plan for insect and human brains is remarkably similar. This common developmental genetic blueprint includes:

- Three foundational regions: In the developing embryo, both insects (protostomes) and humans (deuterostomes) have brains that are patterned into three main segments along the anterior-posterior axis. In insects, these are the protocerebrum, deutocerebrum, and tritocerebrum. In vertebrates like humans, these correspond to the forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain.

- Conserved patterning genes: Key genes, such as otd/Otx and unpg/Gbx, create boundaries and organize the developing brain segments in both insects and humans. Cross-species experiments have shown that insect and mammalian genes from the same family can even replace each other functionally during embryonic brain patterning, further demonstrating their deep homology.

- The midbrain-hindbrain boundary: A key interface between brain regions, known as the deutocerebral-tritocerebral boundary (DTB) in flies and the midbrain-hindbrain boundary (MHB) in vertebrates, is regulated by a homologous set of genes, including Pax2/5/8. These boundary-forming regions eventually give rise to circuits that regulate complex behaviors, including sensory processing, balance, and motor coordination.

Major divergences in brain development and structure

While the genetic toolbox for constructing a brain is shared, the final product is vastly different. Key areas of divergence include:

- Overall size and neuron count: Human brains contain an average of 86 billion neurons, while an insect like a fruit fly has approximately 200,000. This enormous difference in scale allows for the significant cognitive differences between the species.

- Anatomical structure: Though the basic segmented plan is shared, the complex structures built upon it are different. Insects have unique brain regions such as the mushroom body and central complex, while humans have highly complex structures like the prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, and hippocampus.

- Dorsoventral axis inversion: In insects, the main nerve cord is ventral (along the belly), while in humans, the spinal cord is dorsal (along the back). Genetic studies confirm that insects and vertebrates share homologous genes for patterning the dorsoventral axis, but their orientation is inverted, suggesting an evolutionary "flipping" of the body plan after the protostome and deuterostome lineages split.

- Functional decentralization in insects: Insects have a more decentralized nervous system compared to humans. While the brain is the primary command center, insects have multiple ganglia (nerve clusters) throughout their bodies that can independently control local functions. This allows for complex behaviors even when the head is removed in some cases.

Clarification on the outdated "triune brain" model

It is important to distinguish the conserved Tripartite blueprint from the popular but outdated "triune brain" hypothesis

- The misconception: The "triune brain" model, popularized by neuroscientist Paul MacLean in the 1960s, proposed that the human brain evolved in three successive and largely independent layers: a "reptilian complex" (brainstem), a "paleomammalian complex" (limbic system), and a "neomammalian complex" (neocortex).

- Modern refutation: This hierarchical and modular view has been widely dismissed by modern neuroscience. Brain structures do not function independently, but rather as highly interconnected networks. Emotions and cognition are not housed in separate, successively added layers, but are the product of interdependent network activity throughout the brain.

- Correct interpretation: The Tripartite plan found in both insects and humans is a foundational developmental blueprint from a shared common ancestor, not a hierarchical layering of successively evolved parts as MacLean's model proposed.

H.O.B. note: the question to be asked is why the triune brain idea remains so popular and it is not replaced with an equally popular 2, 4, 5, 6, etc., part brain model.

[5] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects of brain neurons"

AI (overview) response: The Tripartite aspect of brain neurons refers to the Tripartite synapse, a concept that recognizes communication at a synapse involves not only the presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons but also the surrounding glial cells, most notably astrocytes. This expanded view has replaced the older "bipartite" model, which focused exclusively on the two neurons.

The three components of a Tripartite synapse interact dynamically and bidirectionally to regulate synaptic information processing, transmission, and plasticity.The three components of a Tripartite synapse

- Presynaptic neuron

- The presynaptic terminal is the transmitting part of the neuron. It releases neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft in response to electrical signals. In the Tripartite model, these neurotransmitters do more than just bind to the postsynaptic neuron; they also signal to the neighboring glia.

- Postsynaptic neuron

- The postsynaptic element, typically a dendritic spine, receives the neurotransmitter signals. In addition to regulating its own activity, the postsynaptic neuron also communicates back to the presynaptic terminal and the surrounding glial cell through various signals.

- Astrocytes (glial cells)

- Astrocytes are non-neuronal "star-shaped" glial cells that are integral to the function of the synapse. Their thin

processes wrap around and physically associate with the pre- and postsynaptic structures, putting them in a prime position to monitor

and modulate synaptic activity.

- Regulating neurotransmitters: Astrocytes express high concentrations of neurotransmitter transporters, especially for glutamate. By taking up excess neurotransmitters from the synaptic cleft, they prevent overstimulation and regulate the duration and strength of the synaptic signal.

- Releasing gliotransmitters: In response to neuronal activity and internal calcium level changes, astrocytes can release their own neuroactive substances called gliotransmitters, such as glutamate, D-serine, and ATP. These gliotransmitters can influence synaptic transmission and plasticity.

- Activity-dependent plasticity: By controlling levels of neurotransmitters and releasing their own signaling molecules, astrocytes participate in synaptic plasticity—the ability of synapses to strengthen or weaken over time. They also play a role in the formation and elimination of synapses during development.

- Astrocytes are non-neuronal "star-shaped" glial cells that are integral to the function of the synapse. Their thin

processes wrap around and physically associate with the pre- and postsynaptic structures, putting them in a prime position to monitor

and modulate synaptic activity.

The consequences of the Tripartite model

The recognition of glial cells as active participants in synaptic function has significantly changed our understanding of the brain:

- Beyond the "neuron doctrine": The Tripartite synapse challenges the old view that brain function arises exclusively from neuronal activity. Instead, it suggests brain function results from the coordinated activity of a neuro-glial network.

- Modulation of brain function: By involving glial cells, brain function is now understood to be more complex, with glial cells helping to regulate synaptic strength, circuit activity, and complex behaviors such as sleep, memory, and cognition.

- Implications for neurological disease: Dysfunctional neuron-glial interactions have been linked to a variety of neurological conditions and disorders, including Alzheimer's, schizophrenia, depression, and epilepsy. Research on the Tripartite synapse offers new avenues for understanding and treating these diseases.

[6] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects of Jungian Archetypes"

AI (overview) response: There is no specific "Tripartite" model of archetypes in Jungian psychology. The "Tripartite" term likely refers to Carl Jung's division of the psyche into three realms—the conscious ego, the personal unconscious, and the collective unconscious—with archetypes residing in the collective unconscious. Jung described numerous archetypes, but paid special attention to four major ones: the Persona, the Shadow, the Anima/Animus, and the Self.

The confusion may also stem from Jung's description of a three-stage individuation process, which involves integrating three specific archetypes: the Shadow, the Anima/Animus, and the Self.The psyche's Tripartite structure

Jung's model of the psyche is often described with these three levels:

- The ego: The conscious mind that organizes our thoughts, feelings, and memories.

- The personal unconscious: A layer just below the ego that contains forgotten or repressed memories and experiences specific to the individual.

- The collective unconscious: A deeper, universal layer of the psyche, inherited by all humans, that contains the archetypes.

The three-stage individuation process

The process of psychological development toward wholeness, or individuation, involves the integration of three key archetypes:

- Stage 1: The Shadow: This archetype represents the hidden, repressed, and unknown aspects of ourselves. It contains our animalistic instincts, weaknesses, and socially unacceptable impulses. Integrating the Shadow requires a moral effort to acknowledge and confront our "dark side".

- Stage 2: The Anima (in men) and Animus (in women): After confronting the Shadow, an individual faces their contrasexual archetype. This inner feminine (anima) or masculine (animus) energy acts as a mediator between the ego and the deeper layers of the collective unconscious. Integrating this archetype allows for a more balanced personality by incorporating qualities like emotion (anima) or logic (animus) that are often suppressed by gender roles.

- Stage 3: The Self: The ultimate goal of individuation, the Self is the archetype of wholeness and unity. Represented often by a mandala, it integrates all the aspects of the psyche—both conscious and unconscious—into a cohesive and balanced identity.

Major archetypes as a triad

While not a formal Tripartite division, these three archetypes represent the major developmental stages of the individual psyche. This process begins with confronting the repressed aspects of one's personality (Shadow), proceeds to integrating one's unconscious feminine or masculine qualities (Anima/Animus), and culminates in the realization of one's full potential (Self).

H.O.B. note: in the following abridged selection using the same query but in the "dive deeper" mode, we encounter a reference to the Trinity and a so-called "missing" fourth aspect, which in my view clearly represents a psychic attentuation to the 3-to-1 ratio, though this labeling is not used.

AI 2nd overview "deep dive" response: There is no singular "Tripartite" model of Jungian archetypes, as Jung's work identifies many different archetypes.

- However, there are three common Tripartite structures that appear in Jungian psychology and its analysis:

- The Tripartite model of the psyche.

- The three archetypes of psychological development.

- Jung's reinterpretation of the Trinity.

Tripartite model of the psyche

This model divides the human psyche into three fundamental, interacting components:

- The conscious mind (Ego): The center of consciousness, composed of our everyday awareness, thoughts, and memories. The ego perceives the world and forms our sense of self.

- The personal unconscious: A reservoir of forgotten, suppressed, or repressed experiences and memories that are unique to the individual. These memories are still readily available to the conscious mind.

- The collective unconscious: The most significant and unique aspect of Jung's theory. This is a shared, inherited reservoir of universal symbols, patterns, and themes—known as archetypes—that exist across all human cultures and transcend personal experience.

Three archetypes of psychological development

In the process of individuation—the lifelong journey toward psychological wholeness—Jung identified three primary archetypes that must be integrated into the conscious personality:

- The Shadow: This archetype is the unconscious, inferior aspect of the personality that a person is unaware of or rejects. Facing and integrating the Shadow is the "apprentice-piece" of psychological development.

- The Anima/Animus: This is the archetype of the soul-image, representing the unconscious contrasexual aspects of the psyche. The anima is the feminine inner personality of a man, and the animus is the masculine inner personality of a woman. Integrating the anima/animus is the "masterpiece" of individuation.

- The Self: This is the final and most important archetype, representing the unification of consciousness and unconsciousness into a harmonious whole. The Self is the ultimate goal of individuation, often symbolized by a circle or a mandala.

H.O.B. note: one might even construct a parallel of the three with the old 3-part system of crafts guilds: Apprentice- Journeyman- Master, or even the current day sociological Tripartiteion of lower- middle- upper classes.

Reinterpretation of the Trinity

In his work, Jung explored the psychological significance of religious dogmas and reinterpreted the Christian Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit from an archetypal perspective:

- The Father and the Son: These represent a masculine dyad or pair of opposing forces, with the Holy Spirit acting as a reconciler between them.

- The Holy Spirit: This archetype acts as the unifying, reconciling element that brings wholeness out of the opposition of the Father and Son.

- The Missing "Fourth": For Jung, the Trinity was an incomplete symbol of wholeness because it lacked a feminine or "dark" element. He argued that a complete symbol for the totality of the human psyche would include a "fourth" element, often representing the feminine (such as Mary or Sophia) or the unconscious dark side. This idea links the Tripartite model of the Trinity to the more complete, four-fold symbol of the Self, often represented by the mandala's quaternity.

[7] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects of Jung's interpretation of the Trinity"

AI (overview) response: Carl Jung interpreted the Christian Trinity as an incomplete symbol of wholeness, arguing that it leaves out a crucial fourth element representing darkness, matter, and the feminine. Through his analysis, the Trinity (three) represents a psychological process of moving from unity to duality and toward a new consciousness, but it fails to achieve the psychological completeness of a quaternity (four).

The Tripartite psychological dynamicJung's analysis treats the Trinity not as a theological reality but as an archetype—a universal, symbolic image that emerges from the collective unconscious. He views the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit as personifications of a three-stage psychological maturation process.

- The Father as original oneness: This stage represents a primordial, undifferentiated state of the psyche, before the emergence of conflict and conscious awareness. The Father is the unreflecting source of all things, similar to an original unitary state of being.

- The Son as duality: The Son's emergence creates a duality by separating from the Father. Christ represents the birth of consciousness, critical reflection, and the struggle with opposites, including the reality of suffering and evil in the world. This increases consciousness but also creates alienation from the original oneness.

- The Holy Spirit as the third element: As the "third term" that proceeds from both the Father and the Son, the Holy Spirit represents the psychological function that resolves the tension of opposites. It is the unifying, reconciling element that restores a sense of lost wholeness, moving beyond the dualism initiated by the Son.

The missing fourth: The move from trinity to quaternity

Jung's critique centers on the Trinity's exclusivity, arguing that for true psychological wholeness, or the archetype of the Self, a fourth, opposing element is necessary. The Trinity is an equilateral triangle representing a provisional unity, but it's not a complete symbol.

The missing fourth element represents all that the Trinity excludes, and its integration is crucial for psychological completeness:

H.O.B. note: The so-called "fourth" element is present when we realize we are dealing with a 3 -in- 1 structure. This 3 -to- 1 ratio is a so-called "fourth" element or identity as part of the developmental scenario of the human psyche as an extention of the underlying biology influenced by the environmental influences of the Sun's three phases/moments. The ideological 3 -in- 1 is a "four" that is acknowledged but is not a separate identity, it reflects an integration.

In other words, "1" is an idea, "2" is an idea, "3" is an idea... and a fusion there of is a 4th idea signifying a coalesence, not a separate individuation, unless comparing some very distant realized human psyche from the triune brain formulations making the ideological circuit today in different forms with different labels.

And a third reference needed to highlight the second in the following bulleted list, his Jung's adaptation of the Tao Te Ching expression "The Dao produced One; One produced Two; Two produced Three; Three produced All things."... Jung frequently borrowed ideas from others and colored them in his own way.

- Evil and the Shadow: Jung argued that the Trinity excluded the element of evil, which he saw as a necessary component for understanding totality. In his work Answer to Job, he explores the idea that Christianity omits the "dark side" of God, which he suggests is necessary for a balanced view of the divine.

- Matter and the Earthly: The Trinity is often conceived as purely spiritual, neglecting the material world. This corresponds to the alchemical axiom of "one becomes two, two becomes three, and out of the third comes the one as the fourth." In this formula, the fourth represents matter, which reintegrates the spiritual into the earthly.

- The Feminine (Mary/Sophia): By emphasizing an exclusively masculine Godhead, the Trinity omits the feminine principle. Jung suggested that the 1950 Catholic dogma of the Assumption of Mary was a significant, albeit tacit, acknowledgment of this missing feminine component, integrating it into the Godhead and moving toward a quaternity.

The Quaternity as a symbol of wholeness

For Jung, the quaternity (often symbolized by a square or circle with a cross) is the superior symbol of psychological wholeness and the Self because it incorporates the opposing and often repressed elements of the unconscious. The dynamic is summarized by the alchemical maxim: "Out of the third comes the one as the fourth." The tension between the opposites (the "two") is resolved by a mediating "third," which in turn creates a transformed state of consciousness—the "one as the fourth," or wholeness. This fourth element brings the divine into incarnated reality, uniting spirit and matter.

rPage initially created: Monday, Sept. 8th, 2025... 1:38 AM

Initial posting: Tuesday, Sept. 9th, 2025... 2:58 AM

Update: Sunday, Sept. 21st, 2025... 1:38 PM