Visitors as of Sept. 3rd, 2025

On this page in order of appearance:

- Tripartite Aspects of Ancient Rulers and Language Experiments: [1]

- Tripartite Aspects of Language Origination: [2]

- Tripartite Aspects of Evolution’s ‘Great Leap Forward’: [3]

- Tripartite Aspects of Audiology and Language Development: [4]

- Tripartite aspects of the 3 types of bilingualism: [5]

- Tripartite Aspects vrs Bipartite Aspects as research parameters: [6]

- Tripartite Aspects of particle Physics and quantum mechanics: [7] (A recognized Tripartite puzzle)

- Tripartite Aspects of Quantum Entanglement: [8]

[1] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects of Ancient Rulers and Language Experiments"

AI (overview) response: A Tripartite social order and ancient language experiments illustrate the intersection of power, societal structure, and inquiry into human nature, with rulers seeking to understand the origins of language to legitimize or extend their authority. While the "Tripartite" social structure of priests, warriors, and commoners arose from Indo-European mythology, ancient kings from various cultures conducted infamous, unethical experiments on infants to discover a "divine" or original language.

The Tripartite nature of ancient rulersThe concept of a ruler whose authority spans three domains is best understood through the trifunctional hypothesis, proposed by French mythographer Georges Dumézil. The hypothesis suggests that ancient Proto-Indo-European societies, and their kings, reflected an ideological division of three functions or castes:

- The first function: Religious and juridical authority, associated with priests. In this role, the king ensured cosmic and social order and communicated with the divine.

- The second function: Military and martial power, associated with the warrior class. The king led his people in war, protected them from external threats, and demonstrated physical prowess.

- The third function: Economic and fertility-related matters, associated with commoners, such as farmers and tradesmen. The king's leadership was tied to the prosperity, well-being, and sustenance of the people.

Later manifestations of this Tripartite kingship appear across diverse cultures:

- Ancient Egypt: The pharaoh was considered a living god or divine agent (first function), commanded the army (second function), and guaranteed the prosperity of Egypt through divine favor (third function).

- Ancient Near East: Kings were seen as the link between the divine and human worlds, receiving revelations and oracles (first function). They served as warlords (second function) and were also responsible for maintaining justice and the rights of the weakest members of society (third function).

- Irish mythology: The sovereignty goddess Morrígan is associated with three aspects of kingship: the king's ascent to power, his rule, and his death.

Language experiments by ancient and medieval rulers

Numerous rulers allegedly commissioned cruel experiments to discover humanity's innate language in pursuit of divine wisdom and imperial supremacy. Examples include:

- Psamtik I of Egypt (7th century BC): Herodotus chronicled this alleged experiment. The pharaoh had two infants raised by a shepherd who was forbidden to speak to them. After two years, the children’s first word, "bekos," was identified as the Phrygian word for "bread," leading Psamtik to conclude that Phrygian was the original language.

- Frederick II (13th-century Holy Roman Emperor): According to the chronicler Salimbene di Adam, Frederick II ordered infants to be raised in silence to see what language they would speak. Salimbene recorded that the babies died, concluding that they "could not live without petting and the joyful expressions and loving gestures of their nurses".

- James IV of Scotland (15th century AD): Records claim the king had two children raised by a mute woman on an isolated island. The children were later reported to have spoken "good Hebrew," although historians were highly skeptical of this finding.

- Akbar the Great (16th-century Mughal emperor): In what is believed to be an authentic experiment, Akbar had infants raised in a "dumb house" by mute wetnurses. After several years, the children could not speak, communicating only with gestures, leading Akbar to conclude that speech was learned.

Thematic connections

The common thread between these themes is the quest for ultimate authority and control. Ancient rulers, often seen as having Tripartite powers combining divine, military, and societal functions, sought to extend their power and validate their rule by searching for a divinely ordained, fundamental language.

- Divine Legitimacy: Kings saw their power as divinely granted (the first function). Uncovering humanity's "original" language was hoped to prove a direct link to the divine and solidify their sacred authority.

- Imperial Supremacy: The language experiments were imperial, not just scientific. The goal was to prove the superiority of a specific language— and by extension, the ruler’s culture— over others, an act of linguistic and political dominance. When Psamtik I concluded Phrygian was the original language, it was a geopolitical setback for Egyptian pride.

- Social Order: Both the Tripartite ideology and the language experiments were attempts to understand and control human nature. The former provided a framework for social hierarchy, while the latter tried to determine whether the foundations of humanity were innate or environmental, a discovery that could be used to manage or control the population.

[2] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects of Language Origination"

AI (overview) response: While a definitive, universally accepted model for the origin of language does not exist, a "Tripartite" (three-part) framework can be used to synthesize the primary components discussed in various academic fields. This framework considers the biological, cognitive, and social factors that collectively led to the development of human language.

1. Biological foundationThis aspect focuses on the physiological and anatomical developments necessary for language production, as well as the neurological changes in the brain.

- Vocal anatomy: Unlike other primates, humans possess a uniquely positioned larynx, a rounded tongue, and a flexible pharynx. These features, in conjunction with refined breath control, allow for a wide range of articulated speech sounds, or phones.

- Neural specialization: The human brain underwent changes that specialized certain regions for language. Evidence of this includes:

- Lateralization: The brain's left hemisphere, in most individuals, became dominant for language.

- Broca's and Wernicke's areas: Specific regions evolved to handle language production (Broca's area) and comprehension (Wernicke's area).

- "Language-ready" brain: This specialization is a key difference from other primates, who use vocalizations that, while neurologically distinct, lack the complex combinatorial abilities of human language.

- Gestural origins: Some theories suggest that language initially developed from gestures, as the brain areas responsible for hand and mouth movements are closely linked. This gestural system would have laid the groundwork for the more advanced neural networks later adapted for vocal language.

2. Cognitive capacity

This aspect explores the mental and psychological abilities that enabled the use of symbols and complex communication.

- Symbolic thought: Crucial to language is the ability to use symbols—sounds, gestures, or signs—to represent objects, ideas, or actions that are not immediately present. The widespread appearance of symbolic artifacts, such as meaningful markings and decorative ochre, in the archaeological record around 100,000 years ago is often cited as evidence of this cognitive leap.

- "Universal grammar": As proposed by linguist Noam Chomsky, humans may be born with an innate capacity for a "universal grammar"—a set of abstract principles that guides and constrains language learning. A sudden, single genetic mutation may have installed this language faculty.

- Mental model construction: The ability to build complex mental models of reality, including discussing past or imagined events, is a foundational cognitive aspect. Language and the brain likely co-evolved, with language itself acting as a powerful new cognitive tool.

3. Social and cultural drivers

This aspect focuses on how the pressures and benefits of social life provided the selective advantages that drove the evolution of language.

- Social cooperation: Language facilitates complex social coordination. It allows for the sharing of knowledge about resources, dangers, and tool-making, which would have offered a strong survival advantage to social groups.

- Grooming and gossip: Robin Dunbar's "gossip and grooming" hypothesis suggests that language evolved to replace physical grooming as a way of maintaining social cohesion in increasingly larger groups. The ability to exchange social information through "gossip" allows a larger number of social bonds to be maintained.

- Reliability and deception: In a socially complex world, communication is not always reliable. Language provides mechanisms for testing, policing, and reinforcing truthfulness, as well as for deceiving others. Theories related to "obligatory reciprocal altruism" examine how language could help track social debts and obligations.

- Cultural transmission: Language provides a mechanism for the rapid and high-fidelity transmission of culture across generations. This includes skills, history, and social norms, allowing for the rapid accumulation of knowledge that is not possible through imitation alone. The resilience of tool cultures in early Homo species, for example, is thought to have required verbal instruction to maintain over long periods.

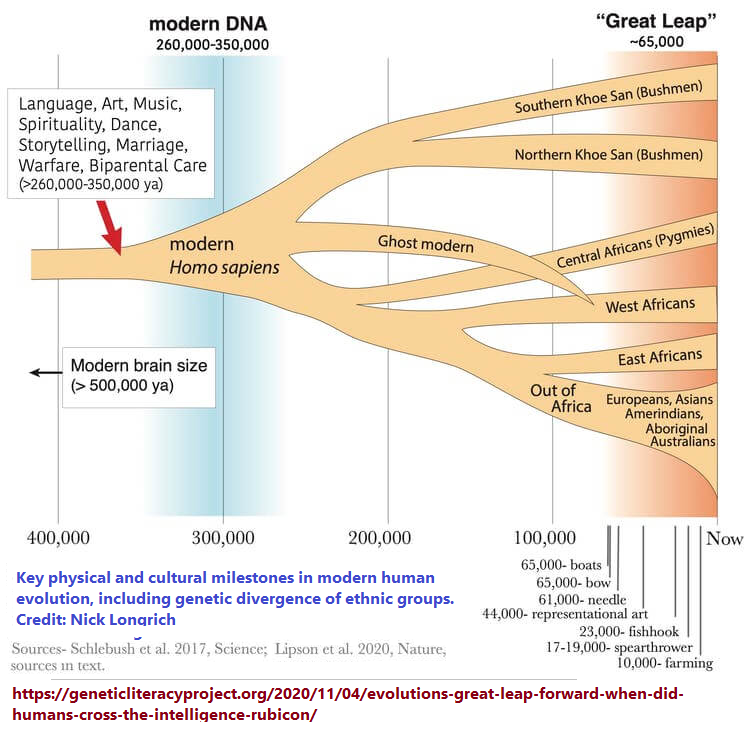

[3] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects of Evolution’s ‘Great Leap Forward’"

AI (overview) response: The evolutionary "Great Leap Forward" refers to a period around 50,000 to 60,000 years ago when the archaeological record shows a sudden and widespread appearance of advanced technologies and culture among early modern humans. A Tripartite, or three-part, framework is often used to characterize the key developments during this time, encompassing cognitive, technological, and social advances.

The three aspects of the evolutionary "Great Leap Forward" are:1. Cognitive advancement: The development of complex, abstract thought

This is the foundational change that enabled all others. It involved the development of modern human cognitive capabilities, which are significantly more complex than those of our hominid ancestors. Key evidence includes:

- Symbolism: The ability to use objects, signs, and images to represent ideas is a hallmark of this period. The creation of non-utilitarian items, like beads and adornments, and the use of pigments suggest that humans were now thinking and communicating in symbolic ways.

- Executive function: Enhanced mental processes allowed for improved planning, focused attention, abstract reasoning, and self-control. This enabled our ancestors to devise and execute more complicated hunting strategies and to adapt to new environments.

- Language: The cognitive capacity for fully modern language, with its ability to convey complex, abstract, and nuanced ideas, is widely seen as a key component of this change. It facilitated the storage and transmission of knowledge across generations, allowing for accelerated cultural evolution.

2. Technological innovation: Sophisticated tools and methods

Following the cognitive shift, the archaeological record shows a dramatic jump in the complexity and variety of human tools and crafts.

- Advanced weaponry: The invention of projectile weapons, such as spear-throwers (atlatls) and the bow and arrow, revolutionized hunting efficiency and safety.

- Specialized tools: Evidence of specialized tools for specific tasks becomes common. This includes items like fishhooks for fishing and sewing needles for creating fitted clothing.

- New materials: Early humans began to incorporate a wider range of materials into their toolkit, such as bone, antlers, and ceramics, rather than relying only on stone.

- Seafaring technology: The arrival of modern humans in Australia around 65,000 years ago provides strong evidence of advanced seafaring capabilities, demonstrating a mastery of new environmental challenges.

3. Cultural expression: The rise of art and interconnected societies

With advanced cognition and technology, humans began to demonstrate new forms of social and cultural behavior that were significantly more complex than before.

- Representational art: This is one of the most visible indicators, with cave paintings, ivory carvings of animals and goddesses, and other representational art becoming common.

- Music: The discovery of flutes made from bird bones points to the emergence of music, an advanced and abstract form of cultural expression.

- Interconnected societies: As population sizes increased and new migration paths were followed out of Africa, humans formed larger, more complex social networks. This increased the rate of invention and cultural transmission through the sharing of ideas, much like a supercomputer is more powerful than a single processor. This social infrastructure is what allowed cultural complexity to emerge and build on itself, rather than individual intelligence alone driving progress.

[4] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects of Audiology and Language Development"

AI (overview) response: The Tripartite aspects of audiology and language development involve the biological, cognitive-linguistic, and social factors that shape a child's communication abilities. For a child with hearing loss, a disruption in one area can profoundly affect the others, making a multi-faceted approach to intervention essential.

1. Biological and auditory aspectsThe biological aspect refers to the physical nature of hearing and how the auditory system functions and develops. Audiology focuses on the assessment and management of hearing loss, recognizing that a child's access to sound is the foundation of spoken language acquisition.

- Mechanics of hearing: The auditory system is responsible for receiving and processing sound. Any impairment can interfere with this process and delay language acquisition. The severity and type of hearing loss (e.g., conductive, sensorineural, or mixed) directly impact how much auditory information a child receives.

- Early intervention: The first few years of life are a critical period for language acquisition. Early identification of hearing loss through universal newborn screening is crucial, as is prompt intervention, including fitting appropriate hearing aids or cochlear implants. This is intended to restore the auditory input needed for the brain to develop language pathways.

- Aural rehabilitation: Audiologists and speech-language pathologists (SLPs) work together on aural rehabilitation, which includes teaching the child how to use hearing technology, training auditory perception, and using visual cues like speechreading to maximize their access to language.

2. Cognitive-linguistic aspects

This aspect covers the mental processes and linguistic structures required for language. Hearing loss affects how a child develops and organizes the complex cognitive and linguistic skills needed for effective communication.

- Vocabulary and syntax: Hearing loss limits a child's exposure to incidental language, or the "overhearing" that accounts for a large portion of early language learning. This can result in a smaller vocabulary, delayed understanding of grammatical rules (morphosyntax), and the use of shorter, simpler sentences.

- Working memory and attention: Children with hearing loss must expend greater effort to listen, especially in noisy environments. This additional cognitive load can tax their working memory and attention, impacting their ability to process and retain language.

- Literacy development: The foundational oral language deficits caused by hearing loss can affect a child's ability to develop strong reading and writing skills. Research shows a strong correlation between early sign language fluency and better literacy outcomes in deaf children, highlighting the importance of a visual language pathway.

- Bimodal-bilingual development: For deaf and hard-of-hearing children, using both a signed language (e.g., American Sign Language) and a spoken language can foster optimal language and cognitive development. This bilingual approach provides full access to a natural language, which can enhance cognitive functions like attention control and problem-solving.

3. Social and environmental aspects

The social dimension recognizes that language is learned and used within social contexts. The child's environment, including the family, peers, and educational setting, plays a critical role in shaping their communication and social skills.

- Family environment: The quality of communication within the family is a major factor in a child's language development. Many deaf children are born to hearing parents who may not be familiar with Deaf culture or sign language, which can lead to unintentional linguistic neglect. Counseling and support are essential to help families make informed decisions about communication methods and create language-rich environments.

- Pragmatic skills: Hearing loss can affect the development of pragmatic language skills, which govern the social rules of conversation. A child might have difficulty interpreting non-verbal cues, knowing when to take a turn, or understanding social nuances, which can limit their participation in social and academic activities.

- Psychosocial well-being: Difficulty communicating can lead to feelings of isolation and social challenges, increasing the risk of psychosocial difficulties and mental health issues. Language proficiency and strong social skills are predictors of better social interactions and are protective against these symptoms.

- Socioeconomic factors: Socioeconomic position can affect access to care, including early diagnosis, hearing aids, cochlear implants, and quality rehabilitation programs. Disparities in these resources can lead to wider gaps in language and academic achievement.

This is for informational purposes only. For medical advice or diagnosis, consult a professional. AI responses may include mistakes.

[5] Internet query: "Tripartite aspects of the 3 types of Bilingualism"

-

3 types of Bilingualism

- Simultaneous bilingualism is when you learn two languages at the same time, with mostly equal emphasis given to both languages.

- An example of this would be a child who grows up speaking both Spanish and German at home, learning both languages simultaneously.

- Successive bilingualism is when a second language is introduced after a first language.

- An example of this would be a child learning Mandarin at home, and subsequently learning English when they begin school.

- Simultaneous bilingualism is when you learn two languages at the same time, with mostly equal emphasis given to both languages.

- Receptive bilingualism is when you can understand two languages but only speak in one.

- An example of this would be a child who is exposed to both French and Arabic at home, and can understand both languages, but only responds in French.

AI (overview) response: The Tripartite, or three-part, aspects of bilingualism are typically described by the categories of compound, coordinate, and subordinate bilingualism. These aspects are defined by the context and age at which the languages are acquired, which affects how the languages are mentally organized and used.

1. Compound bilingualism- Acquisition: A person becomes a compound bilingual by learning two languages simultaneously in the same environment and context, usually from birth or very early childhood.

- Mental organization: Both languages are represented by a single, unified semantic system, but with two different linguistic codes. The bilingual individual has one set of concepts for which they have two words or linguistic expressions.

- Language use: A compound bilingual can often switch between languages with ease and may use them interchangeably, even within the same sentence (known as code-switching).

2. Coordinate bilingualism

- Acquisition: A coordinate bilingual learns the two languages in separate, distinct contexts. For example, a child may learn one language at home and a second, different language at school. This generally happens after they have established proficiency in their first language.

- Mental organization: The languages are stored in two separate and independent mental systems, each with its own concepts and meaning.

- Language use: These individuals may not readily translate between languages because they have two separate conceptual frameworks.

3. Subordinate bilingualism

- Acquisition: A subordinate bilingual typically learns a second language later in life, often as an adult, by filtering it through their more dominant first language. This frequently occurs in a formal learning setting, such as a classroom.

- Mental organization: The second language is not an independent system but is interpreted through the already-established patterns and meanings of the primary language.

- Language use: A subordinate bilingual is generally less proficient in their second language than in their first. They may translate in their head when communicating and might retain a foreign accent.

Limitations of the Tripartite model

While the compound-coordinate-subordinate distinction provides a helpful framework, it is a simplified view of a complex reality. Many bilingual individuals fall somewhere along a spectrum rather than neatly into one category. In the real world, an individual's proficiency and context of use can shift over time, making these classifications more descriptive than absolute.

[6] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects vrs Bipartite Aspects as research parameters"

AI (overview) response: As research parameters, bipartite and Tripartite aspects differ in their number of components or variables, the complexity of the relationships they describe, and their respective applications across disciplines. Bipartite analysis focuses on a two-part relationship, while Tripartite analysis examines a three-part relationship and the interactions among all three components.

Foundational differencesThe core distinction lies in the complexity of the relationships they model.

Disciplinary applications in research

Social and network sciences

- Bipartite networks: Can map collaborations between two distinct groups, such as social organizations and the events they co-sponsor. This approach can reveal which organizations are most central to the events and which events draw the most diverse support.

- Tripartite networks: Can add a third layer, such as funding sources. A Tripartite network could analyze how organizations, events, and funding sources are interconnected, revealing more complex dependency structures.

Philosophy and theology

- Bipartite (dichotomy): Views humanity as consisting of two parts: a material body and an immaterial soul or spirit. Aristotle, for instance, used a bipartite division of the soul into rational and irrational parts.

- Tripartite (trichotomy): Posits three distinct components: body, soul, and spirit. The soul and spirit are seen as separate entities. Plato's Tripartite division of the soul—appetitive, spirited, and rational—corresponds to his political theory of the ideal state.

Physics and quantum mechanics

- Bipartite entanglement: Measures the quantum entanglement between two parts of a quantum system.

- Tripartite entanglement: A more complex measure of "genuine" entanglement that cannot be explained by just the entanglement of two-part subsystems. This is relevant for analyzing entanglement in multi-particle quantum systems.

Ecology and biology

- Bipartite networks: Analyze relationships between two distinct groups of species, such as pollinator-plant or herbivore-plant interactions.

- Tripartite networks: Combine multiple bipartite layers into a single framework. An example is a plant-pollinator-herbivore network, where plants are the central "linking set" that interacts with both pollinators and herbivores.

How to choose your research parameter

The choice between a bipartite and Tripartite approach depends on the complexity of your research question and the nature of the variables.

- Start with a bipartite framework if your initial focus is on a direct, two-way relationship, such as a causal link between two variables. This provides a simpler, clearer model that is easier to test.

- Expand to a Tripartite framework if your initial analysis is insufficient or if you suspect a hidden or mediating variable is at play. Introducing a third component can reveal more intricate relationships and dependencies that a simple two-part model would miss.

[7] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects of particle Physics and quantum mechanics"

AI (overview) response: The Tripartite aspects of particle physics and quantum mechanics refer to specific three-part divisions or relationships that are fundamental to understanding the behavior of matter and energy at the smallest scales. The most prominent examples are the three generations of elementary particles, Tripartite quantum entanglement, and the three-quark structure of baryons.

The Standard Model's three generationsThe Standard Model of particle physics organizes fundamental matter particles, or fermions, into three "generations" or families.

- First Generation: This family is the most stable and makes up all ordinary matter. It consists of the up quark, down quark, electron, and electron neutrino.

- Second and Third Generations: These generations contain heavier, less stable versions of the first-generation particles. For example, the second generation includes the charm quark, strange quark, muon, and muon neutrino. The third includes the top quark, bottom quark, tau, and tau neutrino.

- The Tripartite Mystery: Physicists do not know why matter particles are replicated in three successive generations with increasing mass. The laws of nature seem composed in triplicate for no known reason, a mystery that continues to puzzle physicists.

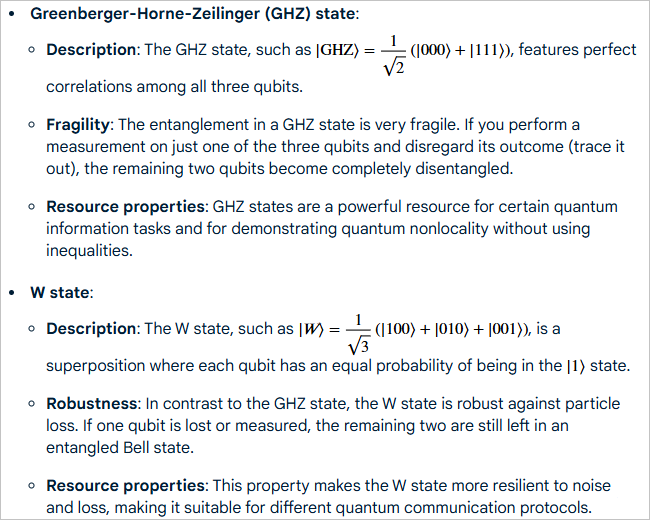

Tripartite quantum entanglement

Quantum entanglement is a phenomenon where two or more particles become linked, with the quantum state of each particle dependent on the others. Tripartite entanglement involves three particles and is a more complex and robust form of entanglement.

- Key Tripartite States: Researchers study different classes of three-particle entangled states, most notably the Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger (GHZ) state and the W state.

- Foundation of Quantum Theory: Genuine Tripartite entanglement is considered a fundamental signature of quantum theory, providing correlations that cannot be explained by any classical or even simpler bipartite (two-particle) theories.

- Applications: This phenomenon is an essential resource for developing quantum information technologies, including quantum teleportation, quantum secret sharing, and quantum computing.

Tripartite quark structure of baryons

In particle physics, the fundamental particles known as quarks combine to form composite particles called hadrons. Baryons are a specific type of hadron formed from three quarks.

- The Proton: A proton is made of two up quarks and one down quark.

- The Neutron: A neutron consists of one up quark and two down quarks.

- Other Baryons: Other baryons, like the various hyperons, also follow this three-quark structure, with different combinations of quark types. This Tripartite structure is a defining feature of baryons.

Beyond the obvious

The concept of a "Tripartite aspect" can also extend to other areas of particle physics and quantum mechanics, though these are less central to the established "Tripartite" topics.

- Three forces in quantum mechanics: From the perspective of quantum mechanics, three of the four fundamental forces (electromagnetism, strong nuclear, and weak nuclear) play significant roles in the subatomic world, while gravity's effects are typically negligible.

- Three-body decays: In high-energy particle physics, certain decays, such as those of heavy fermions and hadrons, involve the decay into three particles. Studying the entanglement between these three particles provides new ways to test the Standard Model and search for new physics.

[8] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects of Quantum Entanglement"

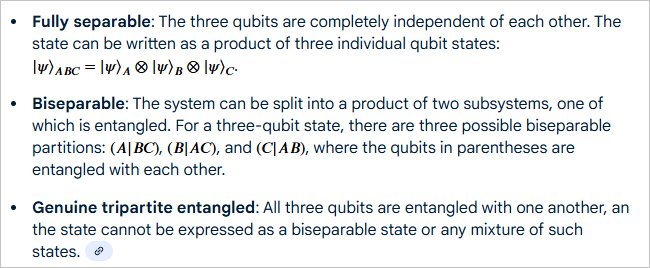

AI (overview) response: Tripartite quantum entanglement is defined by three primary aspects that differentiate it from the simpler bipartite case: the distinct classes of genuinely entangled states, the complex structure of separability, and its unique nonlocality properties.

1. Distinct classes of genuinely entangled statesIn bipartite systems, all maximally entangled pure states (like Bell states) are equivalent and can be transformed into one another using local operations and classical communication (LOCC). For three or more qubits, this is no longer true, giving rise to fundamentally different types of entanglement. For three qubits, the two non-equivalent classes are:

2. Complex structure of separability

For a three-qubit system, entanglement is not a simple all-or-nothing property. Instead, there are multiple layers of separability, creating a more intricate classification hierarchy. A pure three-qubit state can be categorized as:

3. Unique nonlocality properties

Multipartite entanglement reveals nonlocality properties that are more complex than the standard Bell inequalities for bipartite systems. For example, some Tripartite states exhibit genuine multipartite nonlocality, where no local hidden variable (LHV) model can explain the correlations, even if the model is allowed to be nonlocal for some bipartitions.

- GHZ nonlocality: GHZ states were famously used to demonstrate a contradiction between local realism and quantum mechanics without needing statistical inequalities, a result known as the GHZ paradox.

- Svetlichny inequality: This is a specific Bell-type inequality designed to test for genuine Tripartite nonlocality, distinguishing it from states that only exhibit bipartite nonlocality across some partitions. A violation of the Svetlichny inequality proves that the three-party correlations cannot be explained by any combination of local hidden variable theories, even those involving bipartite nonlocal correlations.

- Inequivalence of entanglement and nonlocality: Unlike bipartite entanglement, where all pure entangled states are nonlocal, Tripartite entanglement has surprising features. It has been shown that genuinely multipartite entangled states can exist that do not display genuine multipartite nonlocality. This proves that entanglement and nonlocality are inequivalent for more than two parties.

Page initially created: Thursday, Sept. 4th, 2025... 2:07 AM

Initial posting: Tuesday, Sept. 9th, 2025... 2:46 AM

Update: Sunday, Sept. 21st, 2025... 1:31 PM