Visitors as of Sept. 3rd, 2025

On this page in order of appearance:

- Tripartite Aspects of Monalities: [1]

- Tripartite Aspects of Dualities: [2]

- Tripartite Aspects of Pluralities: [3]

- Tripartite Aspects of Semantics: [4]

- Tripartite Aspects of Noam Chomsky's Linguistics: [5]

- Stephen Pinker vrs Noam Chomsky: [6]

- Tripartite Aspects of Stephen Pinker's Language Theory: [7]

- Tripartite Aspects of Word Order: [8]

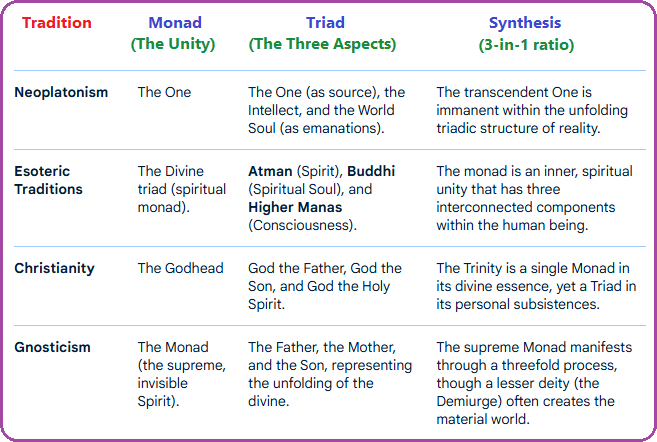

[1] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects of Monalities"

AI (overview) response: The "Tripartite Aspects of Monalities" is not a standard philosophical term, but a conceptual blending of "monads" and "triads," both of which have complex meanings across different philosophical and theological traditions. The phrase likely refers to a conceptual synthesis where an ultimate, indivisible unity (the monad) is understood to manifest or unfold through a threefold structure (the triad).

This concept appears in different contexts, including Neoplatonism, esoteric traditions, and some interpretations of Christian theology.Monads: The principle of ultimate unity

A monad (from the Greek for "unit" or "alone") represents a foundational principle of unity, indivisibility, and totality in various philosophical and mystical systems.

- Pythagoreanism: For the Pythagoreans, the Monad is the first thing to exist, the source of all numbers, points, and geometric forms that make up the cosmos.

- Neoplatonism: The Neoplatonic concept of "the One" is analogous to a monad. It is the ultimate, transcendent source from which all reality emanates. It is beyond being, thought, and language, yet is the foundation of all existence.

- Leibniz: In modern philosophy, Gottfried Leibniz developed a theory of "monads" as fundamental, simple, immaterial, and self-contained substances that make up the universe. Each monad reflects the entire universe from its unique point of view but has "no windows" to be influenced by others.

Triads: The principle of three-part manifestation

A triad is a three-part structure used to explain how unity and multiplicity relate to one another. It describes how an original unity differentiates into three parts to produce all things.

- Platonism: Plato developed a Tripartite theory of the human soul, composed of a rational part (\(Logistikon\)), a spirited part (\(Thymoeides\)), and an appetitive part (\(Epithymetikon\)). For a person to be just, the rational part must rule over the other two. In a different context, the Forms of Truth, Beauty, and Measure (or Proportion) are described as a triad that draws the mind toward the ultimate Form of the Good.

- Neoplatonism: Plotinus and other Neoplatonists explained the process of emanation from the One in a triadic structure:

- The One (Monad): The singular, uncaused source.

- The Intellect (\(Nous\)): The first emanation, which contains the world of Platonic Forms and is pure thought.

- The World Soul (\(Psyche\)): The second emanation, which is the bridge between the perfect, intelligible realm of the Intellect and the physical world.

- Christian Theology: Some Christian traditions maintain a Tripartite (or trichotomic) view of human nature, dividing it into body, soul, and spirit. The Nicene Trinitarian doctrine can also be understood as a triad within a monad: the three persons of the Trinity (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) as a single, unified Godhead.

Synthesis: Tripartite aspects of monalities

Combining these concepts, "Tripartite aspects of monalities" describes how an ultimate unity, or monad, can be understood through a threefold process or structure. This dynamic is a core feature of many esoteric and metaphysical traditions.

In summary, the phrase signifies a metaphysical framework where the singular source of existence expresses itself through a structured, triadic manifestation, linking the ultimate and the contingent in a dynamic relationship.

[2] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects of Dualities"

AI (overview) response: "Tripartite Aspects of Dualities" refers to philosophical or psychological frameworks that use a three-part structure to analyze or mediate a fundamental two-part opposition. These triadic models move beyond simple, polarized pairings to include a third, integrating element that reconciles the two extremes. This concept appears in several fields, from ancient philosophy to modern psychology.

Tripartite models in philosophyPhilosophers have used Tripartite schemes to resolve or explain dualistic problems, particularly the mind-body distinction.

- Plato's dualism and the soul: Plato's theory of the soul is a classic example of this. While he established a mind-body

dualism, he also proposed a Tripartite model for the soul itself.

- The rational soul: Seeks truth and is concerned with reasoning.

- The spirited soul: Responsible for emotions and honor.

- The appetitive soul: Drives desires, urges, and cravings.

- This structure allowed for internal conflict and moral development, with the rational soul striving to rule the appetitive and spirited parts.

- Peirce's categories of reality: The philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce developed a triad of categories to make sense of all

experience.

- Firstness: Possibility, quality, and immediate feeling.

- Secondness: Actuality, reaction, and brute fact.

- Thirdness: Law, habit, and mediation— the integrating element that connects Firstness and Secondness.

Tripartite models in psychology

Depth psychologists have used three-part models of the psyche to explore how the conscious and unconscious mind interact.

- Jung's psyche: Carl Jung proposed a three-part model of the psyche to understand psychological wholeness and individuation.

- Ego: The center of consciousness.

- Personal unconscious: Repressed memories, forgotten experiences, and complexes specific to the individual.

- Collective unconscious: Innate, shared archetypes and instincts that provide a unifying, collective human inheritance.

- Jung saw the process of individuation— attaining psychological harmony— as the integration of the ego with the contents of the collective unconscious.

- The Shadow and the Self: Another Jungian triadic example involves the duality of the conscious ego and the unconscious "Shadow." The Shadow contains repressed, inferior aspects of the personality. The process of integrating these two is mediated by a third entity, the Self, which represents the complete, whole psyche.

Tripartite models in metaphysics and religion

Metaphysical systems, such as Hermeticism, and some religious traditions also use triadic structures to reconcile dualities.

- Hermetic Principle of Polarity: This principle, from the esoteric text The Kybalion, states that "everything is dual" and

that "opposites are identical in nature, but different in degree".

- Polarity: The dualistic pairing, such as "hot" and "cold" or "love" and "hate."

- Degree: The spectrum or continuum between the two poles.

- Mental Alchemy: The Hermetic third aspect is the ability of the mind to consciously change its internal state by "shifting its polarity," moving along the spectrum of degree.

The third aspect: Function and purpose

In all these examples, the third, or "Tripartite," aspect serves a similar function. It is not simply a midpoint between two poles, but an active, mediating, or integrative component that provides a complete understanding of a system or process. It transforms a static duality into a dynamic relationship, often with the following roles:

- Unifying: It provides the container or context (e.g., the Self in Jungian psychology) in which the dual forces can be reconciled.

- Mediating: It acts as a bridge or connector between the dual components (e.g., the energy in the University of Hawaii's "triadic solution" to the mind-body problem).

- Transcending: It offers a higher perspective that re-contextualizes the opposition, revealing that the dual forces are merely different points on the same continuum (e.g., the mental alchemist's perspective in Hermeticism).

[3] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects of Pluralities"

AI (overview) response: The "Tripartite aspects of pluralities" is not a standard philosophical term, but a conceptual combination of ideas from different fields to describe how groups or collections of things can be analyzed through a threefold framework. The idea of a "Tripartite" structure (three parts) is applied to "pluralities," or groups of entities, to understand their internal dynamics and relationships. This framework is most famously seen in Plato's philosophy and appears in various forms in theology, law, and social theory.

Here are the primary philosophical and conceptual interpretations of "Tripartite aspects of pluralities."1. The Tripartite Soul in Plato's Republic

The most influential example comes from Plato's theory of the soul, which he correlates to the ideal city-state.

- The plurality: A person's soul or a city's population.

- The Tripartite aspects:

- Reason (Logistikon): The rational, truth-seeking part that should rule.

- Spirit (Thymoeides): The emotional, honor-loving part that enforces the convictions of reason.

- Appetite (Epithumetikon): The desiring part that seeks physical pleasures and must be kept in check by the other two.

- The dynamic: In a just soul or a just city, these three parts are in harmony, with reason in command. Justice arises from the correct structural relation between the parts, not from any single part's actions.

2. Tripartite theology (trichotomy)

This view holds that human beings are a plurality composed of three distinct, though related, components, often mirroring the Christian Holy Trinity.

- The plurality: Humankind.

- The Tripartite aspects:

- Body: The physical component that interacts with the material world.

- Soul (Psyche): The seat of imagination, emotions, and will, which animates the body.

- Spirit (Pneuma): The part that connects with the divine and the spiritual realm.

3. Social threefolding (Rudolf Steiner)

This social theory proposes that society is a plurality of three independent spheres that must remain distinct to maintain balance.

- The plurality: A healthy society.

- The Tripartite aspects:

- Cultural life: The sphere of art, science, education, and religion, where freedom should be paramount.

- Political life: The sphere of laws and rights, where equality and democratic principles are essential.

- Economic life: The sphere of production, distribution, and consumption of goods, based on cooperation.

4. Legal plurality and plurality decisions

In the context of the U.S. Supreme Court, a plurality decision involves multiple justices who agree on an outcome but not on the legal reasoning, which creates precedential uncertainty.

- The plurality: The collection of justices issuing the decision.

- The Tripartite aspects: The uncertainty of the decision can be analyzed based on three factors:

- Difficulty identifying a single legal rule supported by a majority.

- Difficulty identifying an outcome justified by a single legal rule.

- Difficulty explaining the connection between a single rule and the outcome.

5. Logical pluralism

Some philosophers of logic argue that there is more than one valid standard for logical consequence. A threefold distinction can be used to describe the nature of this plurality.

- The plurality: The differing conceptions of logical validity.

- The Tripartite aspects: Logical pluralism can arise in three distinct dimensions:

- Applicability: Whether a logic can be universally applied or is domain-dependent.

- Semantics: Differences in the meanings assigned to logical terms.

- Nature of validity: The claim that more than one extra-systematic relation can qualify as logical consequence.

ynthesis of the concept

Across these diverse fields, the idea of "Tripartite aspects of pluralities" is a way of organizing a complex whole into a comprehensible three-part structure. The core insight is that for a plurality to function effectively (or for its dysfunction to be understood), its parts must be examined in their specific roles and in their relation to each other. This model moves beyond a simple division of parts, suggesting an intricate, interdependent relationship between distinct, but ultimately connected, components.

[4] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects of Semantics"

AI (overview) response: The "Tripartite Aspects of Semantics" generally refers to the semiotic triangle, a model that illustrates the relationship between the three components involved in meaning: a symbol, the concept in the mind, and the actual object being referred to. Though often attributed to C. K. Ogden and I. A. Richards, it can be traced to earlier philosophers like Aristotle.

The semiotic triangle of meaningThe semiotic triangle illustrates how a word or sign gets its meaning not through a direct, one-to-one relationship with the thing it represents but through a connection mediated by human thought.

- Symbol or Sign: The symbol is the linguistic form used to communicate, such as a word, sound, or image. For example, the spoken or written word "tree" is a symbol.

- Thought or Reference: This is the mental concept or idea that someone associates with the symbol. For the word "tree," this is your mental image or understanding of a tree.

- Referent: This is the actual object or entity in the real world that the symbol refers to. In the example, this would be a physical tree in nature.

In this model, the line between the symbol and the referent is often shown as dotted to emphasize that their relationship is not direct, but depends on the thought that links them.

Charles Sanders Peirce's theory of signs

American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce developed a more complex triadic model of semiotics, defining the relationships as:

- Representamen: The form the sign takes. It could be a word, an image, or a sound.

- Object: What the sign refers to.

- Interpretant: The effect or understanding that the sign produces in the mind of the interpreter. It is a new sign created in the process of interpretation, which itself can become the basis for further interpretation.

Peirce's model classifies signs into three categories based on how they relate to their objects:

- Icons: Signs that signify by resemblance to their objects, such as a portrait or a diagram.

- Indexes: Signs that signify by a direct, causal, or physical connection to their objects, like smoke (index) indicating fire (object).

- Symbols: Signs that have an arbitrary or conventional relationship to their objects, like most words in a language.

Related Tripartite concepts

While the semiotic triangle is the most direct answer, other Tripartite concepts are relevant to the study of meaning and communication.

- Tripartite Structure of Speech Acts: According to speech act theory, an utterance has a three-part structure involving a locutionary act (the act of making a meaningful utterance), an illocutionary act (the speaker's intention), and a perlocutionary act (the effect on the hearer).

- Formal, Lexical, and Conceptual Semantics: Semantics is the linguistic study of how meaning is constructed. Different levels of analysis include the logical structure of formal semantics, the meaning of words in lexical semantics, and the conceptual categories in conceptual semantics.

[5] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects of Noam Chomsky's Linguistics"

AI (overview) response: Noam Chomsky's linguistics can be viewed through a Tripartite framework focusing on three distinct, but related, aspects: the structure of grammar, the nature of language as an internal human capacity, and the fundamental questions that drive linguistic inquiry.

1. Tripartite structure of generative grammarIn his early work, Chomsky proposed that grammar itself is composed of three interacting systems, outlined most famously in his 1957 book Syntactic Structures.

- Phrase-Structure Rules: These rules dictate how sentences are built from smaller units, such as how a noun phrase (NP) and a verb

phrase (VP) combine to form a sentence (S). These rules are hierarchical, not linear, moving from categories to individual words.

- Example: S -> NP VP

- Transformational Rules: These rules explain how more complex or varied sentences are derived from the basic structures generated by the phrase-structure rules. A transformational rule can rearrange, add, or delete elements. This elegantly explains the relationship between sentences like "the man saw the dog" and "the dog was seen by the man," which have the same underlying meaning but different surface forms.

- Morphophonemic Rules: These rules operate at the final stage, converting the abstract grammatical structure into the actual sequence of sounds (phonemes) that are spoken or written. They convert a string of words into their phonetic form.

2. Tripartite nature of language: I-language, E-language, and Universal Grammar

In his later work, Chomsky distinguished between different senses of the word "language" to clarify the proper object of linguistic study, contrasting an internal mental system with an external social one. He then explained that this internal system is constrained by a universal biological endowment.

- I-Language (Internal Language): This is the internal, individual, and intensional system of rules and principles that constitutes a native speaker's knowledge of their language. It is a state of the mind/brain that enables a person to produce and understand an infinite number of sentences. For Chomsky, I-language is the true subject of linguistic inquiry, as it is a real, psychological object.

- E-Language (External Language): This refers to language as an externalized, publicly shared system, such as "English" or "French," or simply a body of observed speech and texts (a corpus). Chomsky argues that E-language is not a coherent scientific concept because it is based on arbitrary, non-linguistic factors (like political borders) and is not uniform across speakers.

- Universal Grammar (UG): UG is the innate, genetically inherited component of the human mind that contains the fundamental principles and constraints shared by all human languages. It is the initial state of the language faculty that allows children to acquire a specific I-language by interacting with linguistic data from their environment. This mechanism resolves the "poverty of the stimulus" problem—the idea that children acquire a rich linguistic competence despite being exposed to a limited and imperfect set of data.

3. Tripartite research program for biolinguistics

In more recent work, Chomsky has framed the study of language within a "biolinguistic" framework, outlining three fundamental research questions for linguistics as a natural science.

- What constitutes the knowledge of language? This question, a direct outcome of the I-language concept, focuses on identifying the specific system of knowledge that exists in the mind of a language user. Answering this involves constructing descriptively and explanatorily adequate grammars.

- How is this knowledge of language acquired? This addresses "Plato's Problem," investigating how a language user's knowledge arises. This area explores how the innate universal grammar interacts with environmental input to produce the mature I-language.

- How is this knowledge of language put to use? This final aspect, concerning "performance," examines how the internal system of knowledge is used in the actual production and comprehension of speech.

[6] Internet query: "Stephen Pinker vrs Noam Chomsky" (This overview is better than that provided by the correct spelling.)

AI (overview) response: Steven Pinker and Noam Chomsky differ significantly in their political and linguistic views, though Pinker was once influenced by Chomsky. Chomsky is known for his anti-establishment political writings and his theory that humans are born with a "Language Acquisition Device" (LAD) for learning language. In contrast, Pinker, a proponent of evolutionary psychology, views language as a biological instinct shaped by natural selection, more akin to a specialized adaptation like a spider's web. Politically, Chomsky's anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist views are well-known, while Pinker's work often engages with social hierarchies and inequalities.

Linguistic Differences- Chomsky's View:

- Argues that children are born with a biological "Language Acquisition Device" (LAD) that provides the fundamental tools for language.

- Pinker's View:

- Believes language is a product of natural selection, an "instinct" or specialized biological adaptation unique to humans, allowing them to communicate effectively.

Political and Social Differences

- Chomsky's Work:

- Characterized by a strong anti-establishment and anti-imperialist stance, challenging power structures and often criticized by the mainstream.

- Pinker's Work:

- Has been described as more aligned with the "establishment," and while not without critique, it tends to be more accepting of social hierarchies and power differences than Chomsky's work.

Relationship & Influence

- Pinker was influenced by Chomsky, among others.

- However, Pinker's views on language and psychology, particularly his evolutionary perspective, differ from Chomsky's influential theories.

[7] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects of Stephen Pinker's Language Theory:"

AI (overview) response: Steven Pinker's theory of language, most famously detailed in The Language Instinct, is centered on the idea that language is a human instinct, wired into our brains by evolution. While not explicitly defining a "Tripartite" model, his work reveals three central, interconnected aspects: the innate universal grammar, language as an evolved adaptation, and language as a window into the broader functioning of the mind.

1. Innate universal grammarThis aspect is heavily influenced by Noam Chomsky, but Pinker places it within an evolutionary framework.

- A blueprint for language: Pinker argues that all human languages share a common, underlying design or blueprint. A baby is not a "blank slate," but rather comes equipped with a pre-programmed set of tools for acquiring language.

- The learning mechanism: According to Pinker, this innate blueprint helps explain how children acquire complex language so quickly and effortlessly, without formal instruction. The "universal grammar" is a mental learning mechanism that recognizes the general rules of speech, like word order, and then begins a very rapid learning process.

- Evidence from creoles: A key piece of evidence for this comes from the spontaneous creation of creole languages. When children are raised in a community speaking a grammatically simplified "pidgin" language, they will invent a new, complex, and precise grammar system, creating a full-blown creole.

2. Language as an evolved biological adaptation

In contrast to Chomsky's skepticism about evolution, Pinker argues that the language faculty itself is an evolutionary adaptation that developed through natural selection.

- Survival advantage: Pinker suggests that the ability to express complex ideas and logic would have provided a significant survival advantage. Language enabled early humans to cooperate more effectively, share information, coordinate hunting, and form alliances.

- The power of communication: This adaptation allowed humans to "shape events in each other's brains with exquisite precision" simply by making noises. It created an information-sharing network that amplified human collective power, as seen in archaeological evidence of ancient cooperation.

- Dedicated neural circuits: Pinker cites neurological evidence to support the idea that language is an evolved trait. He points to specific types of brain damage, known as aphasias, that cause specific language impairments while leaving other cognitive functions intact. This suggests a dedicated, specialized neural network for language.

3. Language as a window into the mind

For Pinker, language is more than just a communication tool; it provides profound insight into human nature, cognition, and how the mind works.

- Revealing thought processes: By analyzing the structure of language, Pinker argues we can better understand how our minds store and process information. Language allows us to glimpse how humans categorize the world, with words showing us what we deem important enough to name.

- Connecting mind and grammar: The ways we organize our sentences, including the use of subjects, objects, verbs, and syntax, reflect the underlying mental machinery. By studying the components of grammar, we can understand the computational processes happening in the brain.

- A key to cognitive science: Pinker's work shows how the study of language is a central pillar of cognitive science, a multidisciplinary field that combines psychology, linguistics, and neuroscience to explain the workings of human intelligence.

[8] Internet query: "Tripartite Aspects of Word Order"

AI (overview) response: While the term "Tripartite aspects of word order" does not refer to a single, specific theory, it accurately describes the three main forces that work together to determine a language's word order: syntax, information structure, and prosody. A sentence's final word arrangement is the result of the interaction between these three distinct factors.

1. Syntactic structure (grammatical functions)This is the most formal and foundational aspect of word order, referring to the grammatical relationships between a sentence's main components. Languages organize their syntax into one of six basic types, with the most common being Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) and Subject-Object-Verb (SOV).

- Subject (S): The agent of the verb.

- Verb (V): The action or state of being.

- Object (O): The patient or recipient of the verb's action.

Example in English (SVO):

- The dog (S) chased (V) the cat (O).

Examples in other languages:

- Japanese (SOV): Inu ga neko o oikaketa. (dog subject-marker cat object-marker chased)

- Classical Arabic (VSO): Qara'a al-waladu al-kitaba. (read the-boy the-book)

2. Information structure (pragmatic functions)

This aspect of word order reflects the speaker's intent and how they organize a sentence to present information as either "given" (known information) or "new" (focused information). In many languages, especially those with more flexible word order, constituents can be moved to highlight certain information.

Key concepts:

- Topic: What the sentence is about; often corresponds to given information and appears at the beginning of a sentence.

- Focus: The most important or new information; can be highlighted in various positions.

- Example in English: While English word order is relatively fixed, changes can shift focus.

- Neutral SVO: Kate ate a piece of cake.

- Fronted object (emphasizing object): A piece of cake, Kate ate.

- Example in Russian: As a flexible-order language, Russian can alter word order to align with information structure.

- Oni podarili emu shchenka. ("They gave him a puppy.") - Neutral word order.

- Shchenka oni podarili emu. ("A puppy they gave him.") - Object-initial to emphasize the gift.

3. Prosody (acoustic and rhythmic functions)

Prosody refers to the rhythm, stress, and intonation of speech. It plays a significant role in determining word order by influencing which parts of a sentence are emphasized. In many languages, there is a natural tendency for new or focused information to receive primary stress, often at the end of a sentence.

How prosody affects word order:

- Nuclear stress rule: In many languages, including English, the main stress in a neutral sentence falls on the final content word. This encourages a word order where the most important or new information is placed last to receive this stress.

- Conflict and resolution: When information structure and prosody conflict with a language's default syntactic word order, it can trigger reordering. For example, to focus on the subject in English, one might use a special intonation, whereas a language like Russian might move the subject to the end of the sentence to align it with the final-focus default.

Interplay of the three aspects

These three elements interact dynamically in language:

- Interaction: Syntax provides the basic framework for ordering, but information structure and prosody can trigger variations or deviations from the default pattern to achieve specific communicative effects.

- Language variation: The specific ways that syntax, information structure, and prosody interact differ from language to language. In English, word order is less flexible, so intonation often marks emphasis. In contrast, languages with rich case systems like Russian have much more flexible word order, allowing movement of phrases for pragmatic purposes.

Page initially created: Tursday, Sept. 4th, 2025... 11:34 PM

Initial posting: Tuesday, Sept. 9th, 2025... 2:44 AM

Update: Sunday, Sept. 21st, 2025... 1:29 PM